Automated Vehicle Technology and Road Safety: Progress Report

It seems that with every exciting step taken towards the autonomous vehicle era, there are countless more questions which arise in respect of road safety, cyber security and, as is the focus of this blog, civil liability and insurance. Whatever your view on these issues, connected and autonomous vehicles are both inevitable and are set to make an enormous impact on our lives in the not too distant future.

Despite many questions remaining unanswered, since I last wrote substantially on this subject the Government has produced the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 which received Royal Assent in July 2018. Furthermore, the Highway Code was updated to reflect changes in vehicle technology. The Act itself is not yet in force and a commencement date is yet to be announced. However, the Law Commission is currently at policy development stage and aims to publish its final report and recommendations by March 2021.

As part of this process, the Commission will be pouring over the Consultation paper responses submitted by stakeholders including the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers (APIL), The Forum of Complex Injury Solicitors (FOCIS), the Bar Council as well as other major players like The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents and Cycle UK – to name but a few.

As the title of the Act suggests, the draft legislation aims to deal with the emerging electric and hydrogen powered vehicle industry and infrastructure (Part 2 of the Act) as well as tackling the existing compulsory third party insurance framework to cover the use of automated vehicles in readiness for their introduction. I do not intend to cover issues relevant to Part 2 here.

The draft legislation

I have previously described how our current law operates when a road traffic accident occurs, including the relevant insurance position and liability considerations. For the purposes of this article, it is sufficient to say that the current legal and insurance framework will not be fit for purpose in the world of autonomous vehicles.

Positively, for those injured in road traffic accidents involving automated vehicles operating when it is not under the immediate physical control of a human being, sections 1 and 2 of the draft legislation creates a direct right of action against the vehicle owner or motor insurer. More reassuring is the fact that the injured party’s route to recovering damages in these circumstances will be via the existing insurance framework thus removing concerns over the Claimant’s need to bring a complex product liability claim against the vehicle manufacturer or indeed any other entity involved in the supply, delivery or maintenance of the automated systems. The simplicity for injured Claimants here was something argued for by APIL during the Consultation and is to be warmly welcomed.

The ‘untidy transition’

Notably however, Part 1 of the draft legislation reflects the future scenario where there is no physical control being exercised or required by a human being while driving. Most will agree we are several years away from this point. Until then we will remain in a period of transition whereby vehicles are partially or conditionally automated i.e. when they are largely capable of steering, accelerating and braking, and avoiding other motor vehicles, but still need a human supervision in case danger arises.

It is deeply concerning then that where a vehicle is largely driving itself but still requires a human being to be alert and ready to intervene at any time, it will be even harder to hold the driver’s concentration. As such, the anticipated ‘safety net’ of a human driver will be deemed ineffectual. It is certainly not difficult to envisage road accidents being caused in this scenario when a human driver fails to react in time, or at all, to a sudden danger or hazard. Indeed, we have already seen examples of the dangers presented when the distinction between automation and human control becomes blurred. In my view manufacturers of semi-autonomous vehicles owe a duty to ensure they are not misleading drivers as to their ongoing responsibility and guard against an over-reliance on the technology.

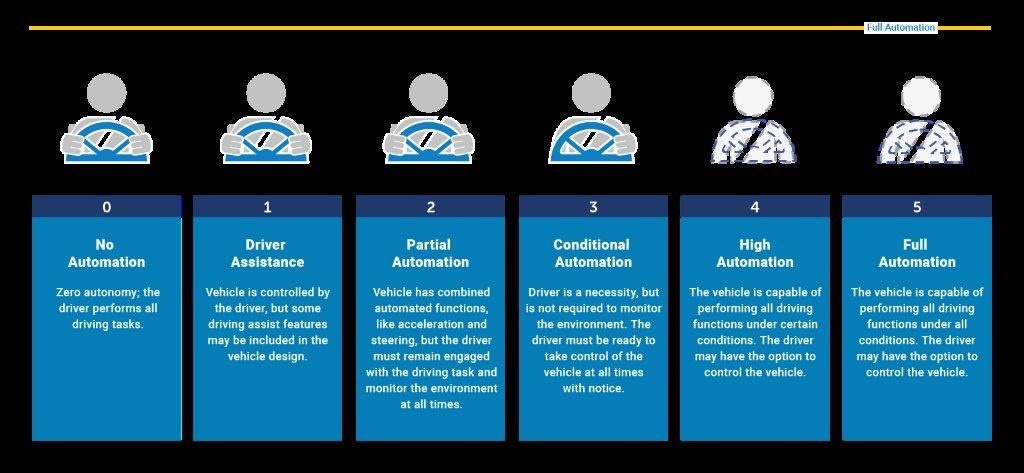

To demonstrate this point further, the image below (produced by the Society for Automotive Engineers) demonstrates the stages of advancement towards fully autonomous driving, whereupon a human driver can safely have hands and eyes off the road (levels 4 & 5), and where we currently are (level 2).

The levels of autonomy involved in driverless vehicles

So, the question remains, what is the legal position during this ‘untidy transition’ where the human driver is still required to operate control of the vehicle even if operating in a semi-autonomous mode? As it is currently drafted, the benefits afforded to those injured in road traffic accidents are confined to those injured by highly or fully automated vehicles. The route to compensation for those injured by vehicles operating in partial or conditional automated modes may find themselves outside the remit of the Act and faced with proving who and what was at fault for the accident.

Both FOCIS and APIL have raised concerns in this regard. In The FOCIS Consultation Response it is stated:

“an area of serious concern is that there is a loophole in the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 which means that the strict liability scheme does not cover vehicles which are on the road currently, which feature partial automation. Those injured by automated vehicles where there is no evidence of fault on the part of a driver currently on the roads will be required to pursue costly and complex product liability claims. It may still be that litigation will involve both driver and manufacturer either because the claimant has to be cautious or indeed the driver or their insurers wish to blame the manufacturer of the car or indeed the software involved leading to lengthy, complex and expensive litigation”.

The future for driverless technology

It remains to be seen whether the Law Commission will act upon the concerns raised in the Consultation Responses about liability during the partial automation phase. In the event it is not, the questions will remain as to the applicability of other areas of law such as the Consumer Protection Act 1987, the law of contract and the law of tort when accidents arise, which is a very unattractive prospect for those who might find themselves injured.

To avoid this, the scope of the 2018 Act must be broadened to factor in all vehicles with automated features, including those where there must be a human monitoring the vehicle in automated mode.

Josh Hughes is a senior associate and Head of the Complex Injury team at Bolt Burdon Kemp. If you or a loved one has been injured as a result of an accident or sub-standard medical treatment, contact Josh free of charge and in confidence on 020 7288 4817 or at joshhughes@boltburdonkemp.co.uk for specialist legal advice. Alternatively, you can complete this form and one of the solicitors in the Complex Injury team will contact you.