Thousands of children in England to miss schooling due to use of “bubbly” concrete

Just days before the start of the new term, dozens of schools have been told to close or limit access due to building safety concerns.

The Department of Education has (31 August 2023) published information for responsible bodies of state-funded education estates in England that are in the process of identifying, suspect they have or have confirmed reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) in their buildings.

The Guidance advises responsible bodies and settings on how to identify RAAC and what they should do if it is confirmed, including vacating and restricting access to the spaces with confirmed RAAC.

Spaces should remain out of use until appropriate mitigations are in place. RAAC has been confirmed in at least 65 schools in England and is suspected in many more.

What is RAAC?

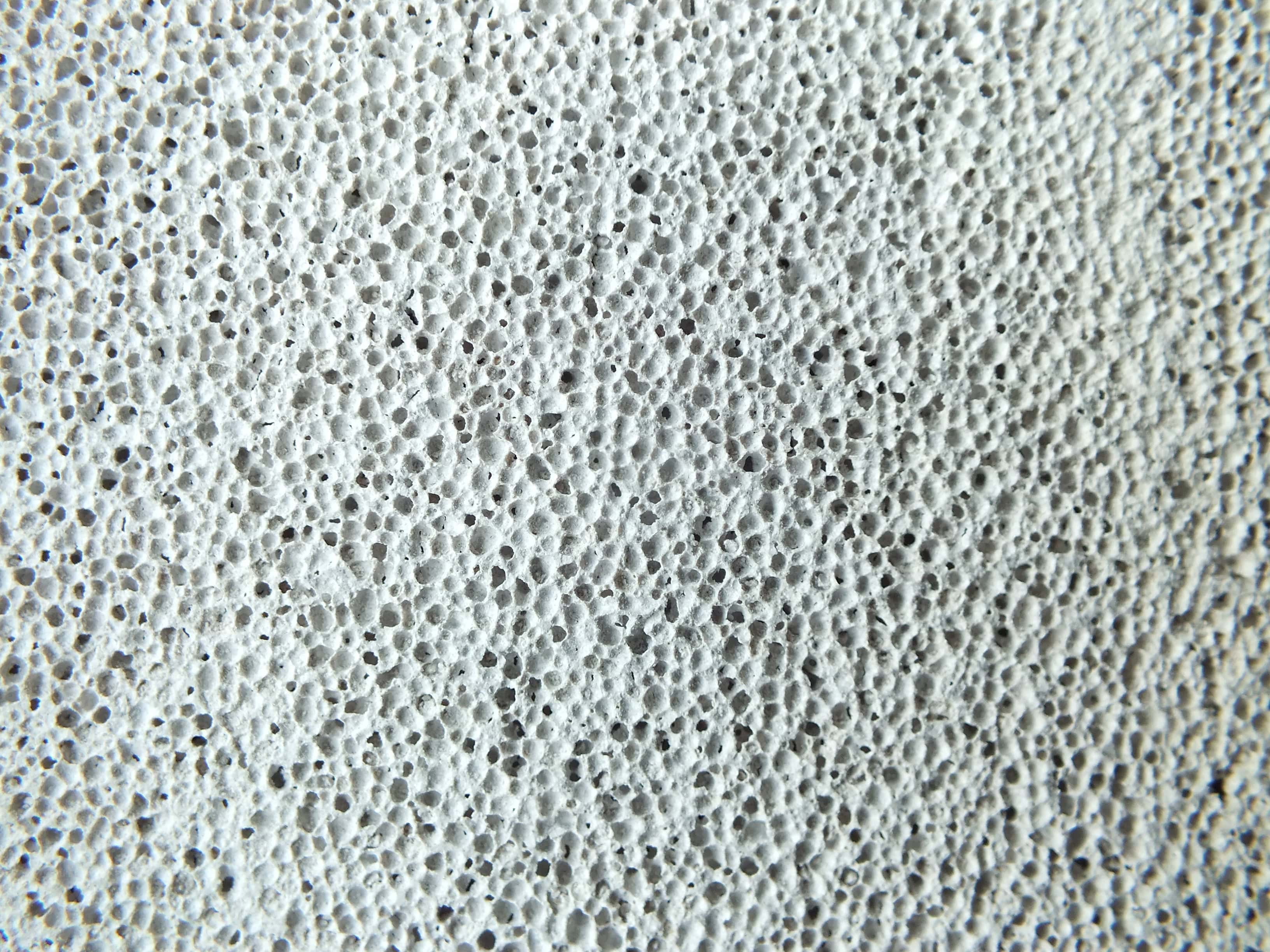

Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (RAAC) is a form of concrete that was used in construction from the 1950s to the mid-1990s (although it has been reported to have still been in use as late as 1998) and widely used in the construction of schools in the UK between the 1960s and 1980s. It consists of a mixture of cement, lime, sand, water and aluminium powder that is cured under heat and pressure to form a lightweight and porous concrete with a “bubbly” texture.

Why is RAAC a potential risk?

Although called “concrete”, it is very different from traditional concrete and, because of the way in which it was made, it is much weaker, having about only10% to 20% of the compressive strength of everyday structural concrete. RAAC is less durable than traditional reinforced concrete, with a useful life estimated to be around 30 years. It’s been known for years, since at least the early 1990s, that it can deteriorate over time, especially when exposed to moisture, fire, or corrosion, without showing visible signs of deterioration, making it prone to sudden failure and leading to structural instability. In the 1980s there were many instances of failure of RAAC roof planks installed during the mid-1960s and a large proportion of such installations were subsequently demolished, although their use in construction continued until at least 1998.

Because RAAC planks were commonly used in roofs, failures, particularly sudden failures, can be catastrophic, posing a serious risk of collapse and potentially resulting in death or injury to students and staff. In 2018, there was a failure of roof planks leading to partial roof collapse at Singlewell Primary School in Gravesend, Kent This happened at a weekend, so the school was fortunately unoccupied. The collapse occurred with little warning. A similar, near failure was reported in 2019 in a retail unit which incorporated the same type of concrete planks. In each case, the consequences could have been more severe, possibly resulting in injuries or fatalities. Following both incidents, full structural surveys found numerous defects in the RAAC planks.

Following the collapse at Singlewell Primary School in 2018, the Local Government Association and the Department for Education contacted all school building owners about the risk and a Standing Committee on Structural Safety (SCOSS) Safety Alert, Failure of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) planks, was issued in May 2019.

Despite long standing concerns about the risks within the construction industry and Government departments, a 2020 survey showed that many schools were not aware that their roofs were constructed using RAAC planks and were therefore not aware of the risks. This is extremely worrying, since pre-1980 RAAC planks are now well past their expected service life. Additionally, it seems that not all structural engineers have appropriate knowledge and experience of how RAAC elements can behave. A CROSS safety report published on 21 August 2023 describes an assessment that may well have been assumed to be competent but was shown by the whistleblower that this was not the case. Building users could be at significant risk of harm if incompetent assessments of RAAC are relied upon. All persons responsible for buildings where RAAC is present, must understand that the assessment of such elements RAAC is a highly specialised area within the structural engineering profession and should only be undertaken by engineers with an appropriate level of skill and experience. Without this understanding of the material, very serious potential structural failures which should have been averted, may be missed.

Although today’s Government guidance is directed at state-funded schools, it is relevant to owners and building managers of all similar buildings dating from the 1960-90s, particularly those with flat roofs. These include Government Departments and Local Authorities who have schools and similar buildings in their asset portfolios. National Health Trusts, Dioceses/Parishes, building surveyors, architects, structural engineers, facilities managers, and maintenance organisations may also be interested. Earlier this year, the government announced that five hospitals deemed at risk of collapse because of deteriorating concrete infrastructure are to be rebuilt. The hospitals – Airedale in West Yorkshire, Queen Elizabeth King’s Lynn in Norfolk, Hinchingbrooke in Cambridgeshire, Mid Cheshire Leighton and Surrey’s Frimley Park – were all built using reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete. At some sites roofs are having to be propped up with scaffolding and posts. The sites have been added to the government’s New Hospital Programme, which the government says will see 40 new hospitals built by 2030. This though includes complete new-builds and sites undergoing major refurbishments and alterations and work has yet to start on 33 of them.

As a solicitor specialising in child brain injury claims, I have seen at firsthand the devastating consequences of serious brain injuries in children and am appalled that through cuts to spending on school buildings and lack of investment in infrastructure children’s safety is being put at risk. It is also deeply saddening that so soon after returning to school from home learning during the Covid pandemic, children’s education is once again being negatively impacted.

Brain injuries in children have lifelong impacts on their physical, cognitive, emotional and social development. They can affect their education, career prospects, relationships and quality of life. Our child brain injury team recently settled a claim for a brain injured child for over £33million. The cost to a single child and their family can far outweigh the remedial work necessary to make our schools safe.

The government and local authorities have a duty of care to ensure that all schools are safe and fit for purpose. They should conduct regular inspections and surveys of buildings and take immediate action to repair or replace them if they are found to be unsafe. We owe it to our children.