Neonatal assessment and the importance of colour: ensuring fair care for all

At Bolt Burdon Kemp (BBK), we believe that every child deserves fair and equitable care, regardless of their ethnic background. Sadly, this is often not the case.

Today, I want to shed light on an important issue concerning neonatal assessment, particularly for families of Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) origin. This follows the recent publication (in July 2023) of the Review of neonatal assessment and practice in Black, Asian, and minority ethnic newborns by the NHS Race and Health Observatory. The Review raises significant concerns around the assessment of skin colour in Black, Asian, and minority ethnic neonates.

As Head of the Child Brain Injury Team at BBK, I want to empower all families with information that could be vital for their child’s well-being. Understanding the limitations of standard NICE Guidelines on neonatal assessments, particularly in their use of language and terminology to describe colour, could be key to getting your child the help they need, where there has been a failure to diagnose a serious condition leading to brain injury.

What is a neonatal assessment?

A neonatal assessment is used to evaluate the overall health and well-being of a newborn baby. The assessment is typically performed by healthcare professionals, including doctors, nurses, or midwives, experienced in neonatal care. The specific components and depth of the neonatal assessment may vary depending on the baby’s clinical condition, risk factors, and any specific concerns identified during the evaluation.

A comprehensive neonatal assessment has several key elements including:

- Measurement of vital signs such as heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and temperature to assess the baby’s cardiovascular and respiratory status.

- A thorough examination of the baby’s body to check for any physical abnormalities, birth injuries, or signs of distress.

- Determination of the baby’s gestational age based on physical characteristics, such as size, appearance, skin texture, and maturity of certain developmental features.

- Measurement of the baby’s weight, length, and head circumference to assess growth and monitor for any abnormalities.

- Evaluation of the baby’s ability to latch onto the breast or bottle, suck effectively, and swallow without difficulty, to ensure adequate nutrition and hydration.

- Evaluation of the baby’s neurological development, reflexes, muscle tone, and response to stimuli to assess the baby’s nervous system function and identify any abnormalities or signs of neurological disorders.

- Inspection of the baby’s eyes for any abnormalities or signs of eye-related conditions.

Laboratory tests may be warranted depending on the baby’s clinical condition, risk factors and any specific concerns identified during the evaluation.

The APGAR Score

A quicker assessment, known as an APGAR score, was developed in 1952 by Dr Virginia Apgar, a white American anaesthetist. Her system was designed to assess the health and well-being of newborn babies at 1 and 5 minutes after birth and in response to resuscitation.

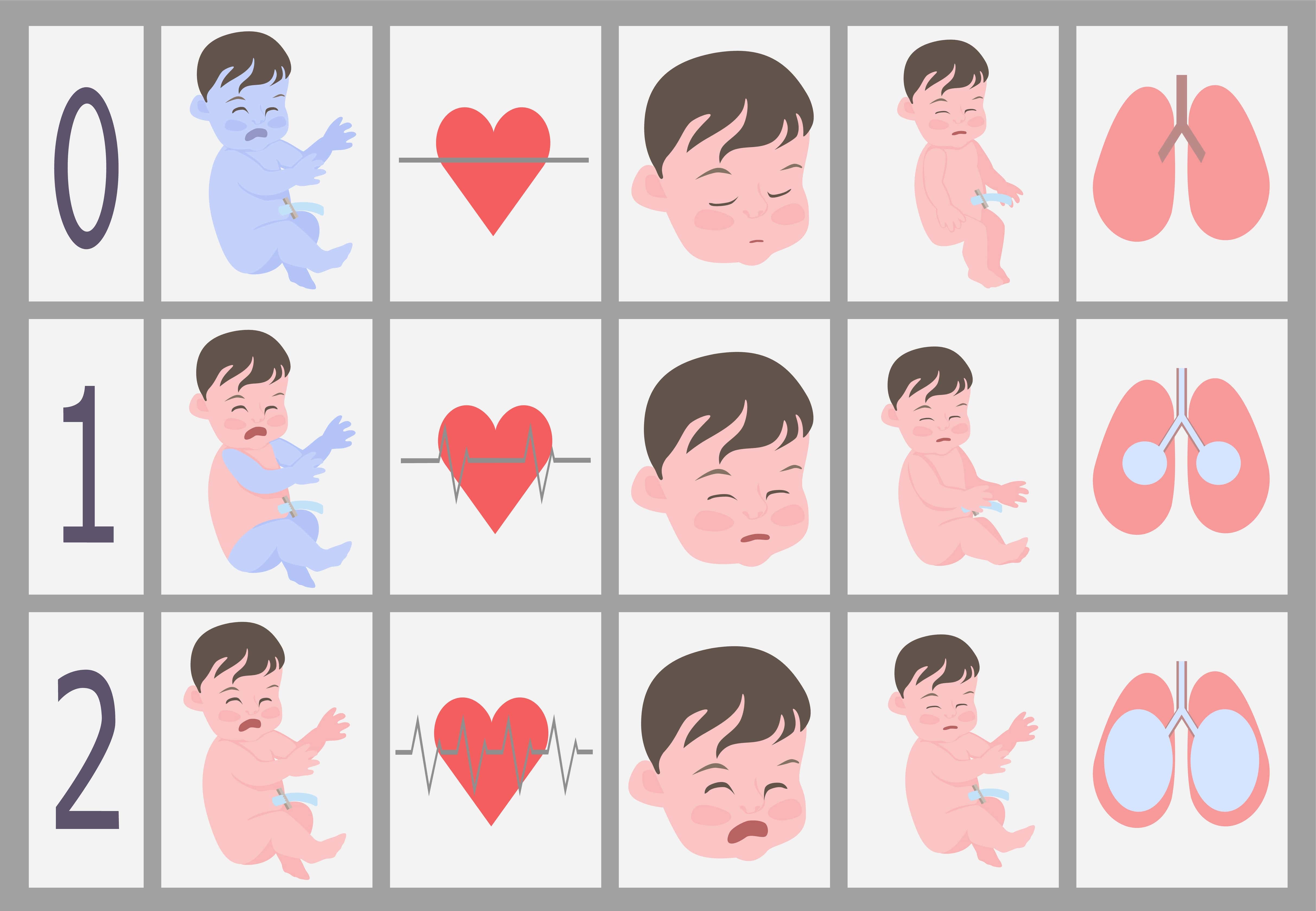

The system is widely used around the world and evaluates five factors—Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, and Respiration—assigning a score of 0, 1, or 2 to each factor with a maximum total score of 10. The total score provides a quick snapshot of the newborn’s immediate condition and helps medical professionals determine if the baby requires urgent medical attention or further observation.

Criticisms of the APGAR Score terminology

The APGAR assessment has been criticised for its limitations when applied to children of Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) neonates. Some of the criticisms relate to its limited relevance to certain conditions such as sickle cell disease, and its failure to take account of social factors, among others. However, the limitation I want to focus on in this blog is its inherent skin colour bias.

The APGAR assessment includes the factor of “Appearance” and evaluates this based on visual observation by the healthcare provider, who is asked to determine whether the baby’s skin appears pale or blue (indicating poor oxygenation) or if it has a healthy pink colour (indicating good oxygenation). A score of 0, one, or two is assigned based on the observed appearance, with two indicating a normal pink colour and good oxygenation.

Clearly, this scoring system does not adequately account for different skin tones, potentially leading to misinterpretations and delayed or missed diagnoses. Two serious conditions, with potentially devastating long-term consequences, that depend on accurate assessment of skin colour, are jaundice and cyanosis.

What is jaundice and what are the consequence of failing to diagnose and treat it?

Jaundice in newborn babies is relatively common. It is a medical condition characterised by yellowing of the skin, eyes, and mucous membranes. It occurs when there is an excess buildup of bilirubin (a yellow pigment produced by the breakdown of red blood cells) in the bloodstream. Normally, the liver processes and eliminates bilirubin from the body. However, if there is an issue with the liver’s function or if there is an excessive breakdown of red blood cells, bilirubin levels can rise, leading to jaundice.

High bilirubin levels can be toxic to the developing brain so it’s essential to monitor and manage neonatal jaundice appropriately. Treatment may involve phototherapy (exposure to special lights) or, in severe cases, exchange transfusion to remove and replace the baby’s blood.

A failure to diagnose and treat jaundice promptly can result in long-term neurological problems such as cognitive impairments, developmental delays, hearing loss and vision problems, and movement disorders such as cerebral palsy. It can also cause lethargy and decrease a baby’s appetite leading to poor feeding and inadequate weight gain.

What is cyanosis and what are the consequences of failing to diagnosis and treat it?

Cyanosis is a medical term used to describe a bluish or purplish discolouration of the skin, lips, and mucous membranes. It occurs when there is an inadequate amount of oxygenated blood circulating in the body. When the oxygen levels in the blood are low, the colour of the blood appears darker, leading to the bluish discolouration.

Cyanosis is a sign that something may be affecting the oxygenation of the blood and it can indicate the presence of a potentially serious and life-threatening condition requiring immediate evaluation and urgent intervention.

Failure to diagnose and address cyanosis in newborn babies promptly can have serious consequences. The baby’s brain, heart and other vital organs are particularly susceptible to injury due to inadequate oxygen supply. Prolonged oxygen deprivation can lead to Hypoxic Ischaemic Encephalopathy (HIE) resulting in long-term neurological impairments, such as cognitive deficits, developmental delays, learning and physical disabilities, and seizures. It can also lead to metabolic disturbances with similar consequences. It can also lead to multi-organ dysfunction. Neonatal cyanosis can also be a symptom of various underlying conditions, such as congenital heart defects, respiratory disorders, or metabolic abnormalities. Failure to diagnose cyanosis may result in delayed identification and treatment of these underlying causes, potentially leading to further complications and health risks.

The problem

It is crucial for healthcare providers to diagnose, monitor and manage neonatal jaundice and cyanosis appropriately to prevent potentially devastating long-term effects on the baby’s health and development.

The problem is that for an assessment based on visual observation current terminology, describing skin as “pink”, “blue” or “yellow”, is simply not appropriate for babies of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic families and can lead to missed or delayed diagnosis of jaundice and cyanosis which are preventable causes of brain injury in children.

The consequences for the child and their family of a missed or delayed diagnosis of jaundice or cyanosis leading to a brain injury are profound. There may be a need for specialist care, equipment, learning support, accommodation, and therapies, on top of financial worries and emotional distress. Any delay in diagnosing the brain injury itself compounds the problem by, in turn, delaying or preventing access to the early support and rehabilitation that is key to maximising the child’s quality of life and enabling them to fulfil their potential.

What can be done?

The skin colour bias inherent in the current APGAR score system and in the identification of jaundice must change. The RHO review makes multiple recommendations for practice that, if adopted, have the potential to decrease health inequalities and ensure safe care for all. These include the wider use of devices such as bilirubinometers and pulse oximeters.

It is encouraging that efforts are being made to address the limitations of neonatal assessment to ensure that all children, regardless of their ethnic background, receive fair and equitable care from the very beginning. However, the inadequacy of the assessment criteria has been known “for decades” according to Dr Shabna Begum, co-chief executive of the Runnymede Trust, so these changes will come far too late for far too many.

Legal Remedies and Compensation

If your child has suffered a serious brain injury because of inappropriate neonatal assessment, there may be legal avenues available to seek compensation. Healthcare providers have a duty to ensure that assessments and guidelines are inclusive, considering the unique characteristics and needs of all children.

If you believe that inappropriate neonatal assessment has led to a serious brain injury for your child, we are here to help. Our dedicated Child Brain Injury Team is experienced in representing children of families who have faced similar challenges, including cases involving clinical negligence related to maternity and neonatal care.

We believe every child deserves the best possible start in life.

Claudia Hillemand is a partner and head of the Child Brain Injury Team at Bolt Burdon Kemp.