Groundhog Day: Why isn’t the NHS testing mothers for Strep B infection?

In February 2020 I tasked myself with writing about Group B Strep infection in babies for our webpages. This was prompted mainly by two things. I specialise in acting for those who have suffered catastrophic brain injury as babies or children, so I’m always investigating how those injuries could have been avoided, and rejoice if developments in health care or health and safety have the potential to reduce or eliminate the risk of other babies and children suffering similar devastating injuries in the future. Then, towards the end of 2019, the Government announced that ethical approval has been given for a £2.8 million trial to prevent Group B Strep being passed on to newborn babies. The trial, to be known as GBS3, was to start in Spring 2020 and would look at the effectiveness of two different tests for Group B Strep (or GBS for short) compared with “standard care”. Group B Strep is the most common cause of life-threatening infection in newborn babies, causing a range of serious infections including pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis, leading to death or lifelong disabilities, so anything that can prevent these infections is “A Good Thing” in my book. But I couldn’t understand why the NHS didn’t already routinely offer tests to all mothers to be for Group B Strep. The tests seemed to be relatively cheap and could lead to antibiotic treatment that would prevent babies from dying or becoming disabled. There must be a reason. I decided to find out and write about it.

Things didn’t go according to plan because on 11th March 2020 the World Health Organisation declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a pandemic and along with billions of others, I had other priorities.

Nearly 12 months later, on 2nd February 2021, which as everyone knows is Groundhog Day, I read an article by Kat Lay, the Times Health Editor that “the vast majority of hospitals across the UK have failed to adopt an £11 test to detect whether pregnant women are carrying this potentially deadly bacteria, despite national guidelines”. So, in the year since February 2020, countries across the world have mobilised resources to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, to research transmission, prevention, vaccines, medicines and treatments, to study and understand the virus and disease progression, to undertake hundreds of clinical trials, and have developed, authorised for emergency or full use and deployed no less than nine vaccines. Yet, we in the UK are no further on in the detection and prevention of Group B Strep infection than a year ago.

I understand that there are cost/benefit factors at play and that, for many, the great threat to global prosperity and well-being posed by Covid-19 justifies the resources employed. On 25th November 2020, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which keeps track of UK government spending, estimated that borrowing for the financial year (April 2020 to April 2021) would be £394bn (the highest ever seen outside wartime). In comparison, before the crisis the government had been expecting to borrow about £55bn for the financial year.

But everything is relative, and it’s surely worth thinking about some of the cost/benefit factors at play around an £11 test for Group B Strep.

What is Group B Strep?

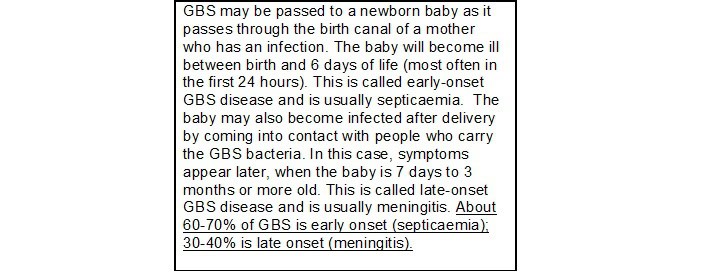

Group B streptococcus (Group B strep or GBS for short) is a type of bacteria. It lives in the intestines, rectum and vagina of about 20-40% of women in the UK. In general, women carrying, or colonised by GBS will have no symptoms or problems and, if pregnant, will go on to have a healthy baby. Occasionally, however, GBS can lead to GBS infection, which can cause serious illness for the newborn baby, because their immune systems have not had time to develop. GBS can cause serious illness in babies, such as meningitis, septicaemia or pneumonia. In fact, GBS infection is the leading cause of sepsis and meningitis in new-borns in England.

The day before I read the article by Kat Lay, I was fortunate to have the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine and as a result I’m now substantially less likely to become seriously unwell with COVID-19 or to transmit the virus. Unfortunately, there is currently no vaccine to protect against GBS disease and, unless detected and treated early with antibiotics, it can lead to the baby suffering lifelong serious disabilities or dying.

What cost to the child – and his or her family?

To illustrate the effect of a lifelong disability on the child and or their family, and the cost of meeting the needs arising from those disabilities, let’s look at a real case. It’s a case that settled in 2018, when the child had reached adulthood and was aged 20.

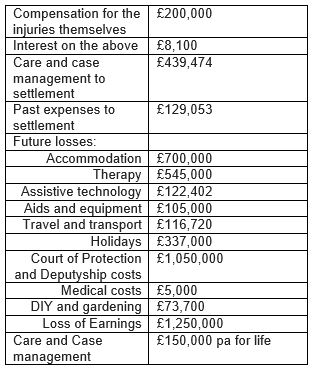

BZE, was born in 1998 and is now in his 20s. As a baby, he developed GBS meningitis and a subsequent brain injury, which resulted in cerebral palsy. He was diagnosed with a learning disorder, with global developmental delay, cortical visual difficulties and autistic spectrum (social and communication) disorder, as well as behavioural difficulties. He has a mild motor disorder with upper limb and co-ordination impairments. He has intermittent incontinence and impaired speech. His condition is permanent. He has a normal life expectancy, and so will outlive his parents. Because of his severe cognitive defects he cannot dress or wash himself or prepare meals; he can walk and does not need to use a wheelchair.

He remains totally dependent on 24 hour care and will continue to need this throughout his life. He has needed – and will continue to need – therapy, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy. A case manager is needed to manage the care and therapy team. He requires suitable accommodation for himself and the care team. He has needed and will continue to need aids and equipment. He and his family have had to attend medical and therapy appointments, incurring travel expenses. His holidays will be more expensive because he will need to take carers with him. He is not able to manage his financial affairs and will need to pay for Court of Protection and Deputyship costs. He will have medical costs. He is not able to do any DIY or gardening to maintain his home so this must be paid for. He has substantial assistive technology needs. He will never be capable of employment. He will never live independently.

The Defendant accepted that there had been a negligent delay in giving antibiotics to BZE in the early neonatal period and also accepted that, had antibiotics been given in a timely manner, BZE would have avoided developing GBS meningitis and the subsequent brain injury. The court approved a settlement of his claim for compensation, which was valued as follows:

Overall, BZE was awarded £5,200,000.00 as a lump sum, (£5,406,828.58 in today’s terms) plus periodical payments of £150,000.00 (index linked) every year for as long as he lives, to compensate him for his injuries caused by GBS and for the losses and expenses that followed as a result.

It must not be forgotten: this is not a “win”, as many media outlets suggest with depressing regularity. No, it is desperately needed compensation intended to put the injured person in the position they would have been in had they not been injured, insofar as money can do that. Of course, no amount of financial compensation can take away BZE’s lifelong learning disabilities, visual difficulties, social and communication disorder, behavioural difficulties or physical impairments, incontinence or impaired speech, loss of independence and enjoyment of the possibilities of life. But it can provide security, alleviating worry for his parents and a quality of life not otherwise possible.

The point is, that the cost to BZE and his family of a serious lifelong disability are immense and seem, to me at least, to outweigh the £11.00 cost of the test needed to detect GBS in the mother and the modest costs of the antibiotics needed to treat the infection.

What cost overall?

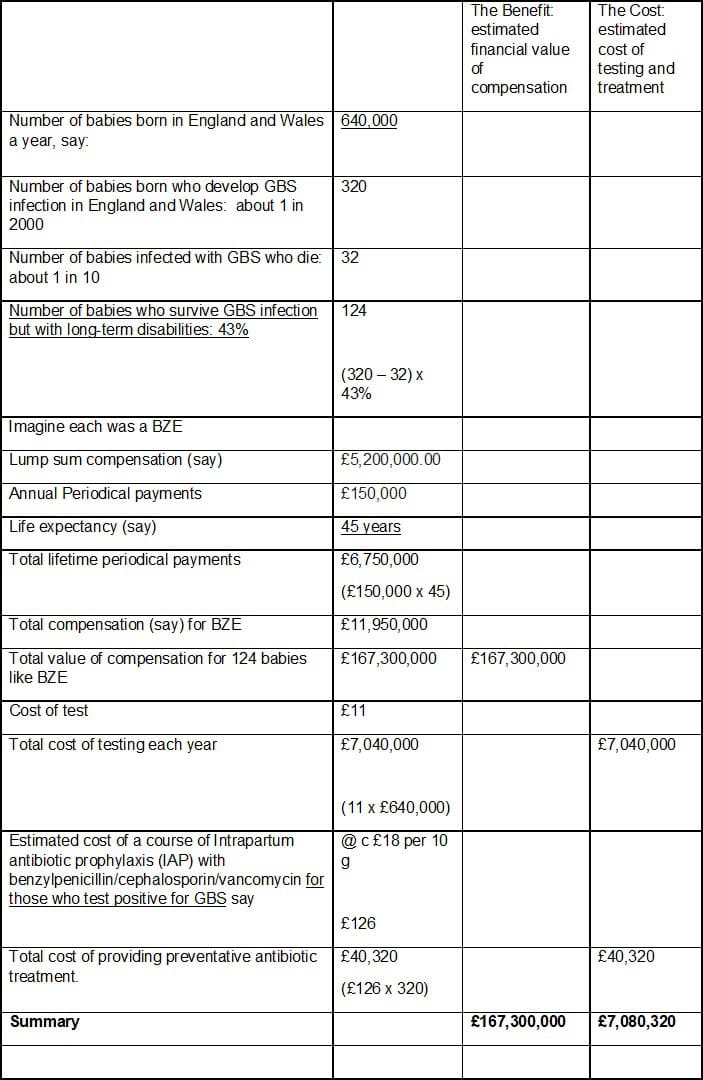

There’s a huge field of research devoted to evaluating quality of life to inform health decision-makers, such as the European Medicines Agency or the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, when they come to try to balance the relationship between cost and value when making economic decisions about access to tests or drugs. I don’t pretend to have any qualifications in this field at all. But as a lay person, I find it hard to understand why there exists such an apparent imbalance in the numbers:

These numbers don’t take into account the many millions of pounds of NHS health care costs required to treat early onset GBS infection, the vast sums needed to provide educational support, nor the eye watering level of legal costs incurred by the NHS Resolution in defending cases like BZE’s.

So, on the face of it, for the £7million cost of GBS testing of all mothers to be each year and of providing preventative antibiotic treatment for those found to be carrying an infection, there is the potential benefit of avoiding £167,300,000.00 worth of pain, suffering, loss and expense, not to mention statutory health, education, social and legal costs. One hundred and sixty seven million (at least) vs seven million.

Why test?

In BZE’s case, the Defendant accepted that there had been, not just a delay, but a negligent delay in giving antibiotics to BZE in the early neonatal period and also accepted that, had antibiotics been given in a timely manner, BZE would have avoided developing GBS meningitis and the subsequent brain injury. Some delays are not negligent and if there is no negligence there is no compensation. One of the many challenges in deciding whether there has been a negligent delay arises from the fact that the signs and symptoms of meningitis or septicaemia are often non-specific especially at first and can be difficult to recognise in very young babies.

Signs and symptoms can include:

- Fever (can also have cold hands and feet)

- Reluctance to feed

- Vomiting and/or diarrhoea

- Irritability/dislike being handled

- Floppy/difficult to wake/unresponsive

- Difficulties breathing or grunting

- Faster or slower than normal breathing rate

- Pale/blotchy skin

- Red/purple spots/rash that do not fade under pressure

- High pitched cry/moaning/whimpering

- Bulging fontanelle (soft spot)

- Convulsions/seizures

- Arched back

- Swollen abdomen

- Dry nappies

Source: Meningitis Now

A baby may have a fever, or be reluctant to feed or have vomiting and diarrhoea for any number of reasons and if a responsible body of medical opinion would not recognise these as signs of meningitis or septicaemia, failure to do so cannot be said to be negligent.

But as a delay in recognising these signs could have such serious consequences, why not test the mother for GBS colonisation in any event, to be forewarned of any increased risk and start immediate antibiotic treatment?

What tests are available?

According to Group B Strep Support (GBSS), the world’s leading charity working to eradicate Group B Strep infection in babies, there are two tests commonly used within the NHS to detect which mothers to be are Group B Strep carriers.

One is the standard ‘non-selective’ swab test, known as the High Vaginal Swab (HVS) test. This is a general-purpose test, not specifically designed to detect Group B Step bacteria. Though it will detect GBS sometimes, it often misses them. So, a positive Group B Strep result from an HVS test is reliable but a negative test result is not.

The other test commonly used is a Group B Strep-specific swab test, known as the Enriched Culture Medium (ECM) test. This is specifically designed to detect Group B Strep and, when properly performed at the right time, is highly reliable. This test is considered the “Gold Standard” for GBS testing.

There are other tests too. Urine tests of cultured urine sample may find Group B Strep in urine indicating a GBS urinary tract infection. Importantly, a negative urine test only indicates that there is no Group B Strep in urine. It may still be present in the vagina or rectum. There is also a test known as a Rapid or “Bedside” test, which can give a fast result (in 50 minutes or less) using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method on the labour ward itself, but this test is rarely used in the UK outside of research trials.

Arguments against testing

This is a highly controversial issue. Despite its availability and reliability and although it’s widely available in other first world countries, the UK National Screening Committee (UKNSC) doesn’t recommend routine screening with the “Gold Standard” ECM test in the UK because:

- a woman may have a positive result a few weeks before labour and a negative result when she gives birth

- GBS does not cause an infection in every baby – there is no way of telling which babies will be affected

- screening may result in giving many women antibiotics when they do not need them

- it is not known if the benefits of screening outweigh the harms for most of the population

- the proportion of babies affected by disease in countries where screening is carried out is similar to that in the UK

The GBSS offers firm rebuttals to these arguments. In particular, in response to the UKNSC’s assertion that screening may result in giving many women antibiotics when they do not need them, GBSS states:

“Research found that a similar number of women would be offered antibiotics if we screened women compared with the risk-based approach. The key difference is that with screening they would be offered to the women most likely to be carrying GBS in labour, rather than to women who have risk factors which are very poor at predicting GBS carriage (a recent study found that two-thirds of the newborn babies who developed GBS infection had no risk factors).

“For newborn babies the consequences of their mother not having preventative antibiotics in labour if she’s carrying GBS can be catastrophic – sepsis, meningitis or pneumonia. The potential benefit of the antibiotics far outweighs the potential risk. Antibiotics have been proven to be highly effective at stopping GBS infections in newborn babies when given intravenously to the pregnant woman as soon as her waters have broken, or labour has started.”

So, the issue remains “live”. The fact is that most high-income countries do offer universal testing to pregnant women, and the GBS3 trial for which funding was approved towards the end of 2019, is going to examine the evidence to establish the best approach for the UK. Specifically, the GBS3 trial will be looking at whether testing pregnant women Group B Streptococcus reduces the risk of infection in newborn babies compared to the current UK strategy.

What is the current UK strategy?

The current strategy recommended by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), and adopted across the UK, essentially involves identifying risk factors in the mother for their baby developing group B Strep (GBS) infection and offering intravenous antibiotics in labour if:

- the baby is born preterm (before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy) – the earlier the baby is born, the greater the risk

- the mother has previously had a baby affected by GBS infection

- the mother has had a high temperature or other signs of infection during labour

- the mother has had any positive urine or swab test for GBS in this pregnancy

- the mother’s waters have broken more than 24 hours before her baby is born

In late 2017, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists updated their guidance and recommended that women who tested positive in their previous pregnancy should be offered testing specifically for GBS, in their next pregnancy. But, and this is the point that Kat Lay was making in February 2021, only a tiny number of NHS Trusts, according to the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) are following the key new recommendations around giving pregnant women information on group B Strep, offering testing to some pregnant women, and following Public Health England (PHE) guidelines on testing for group B Strep.

The risk of a risk based approach to GBS is that opportunities to prevent and treat GBS infections are missed. The same opportunities are missed if guidelines for providing information and testing are not followed.

Missed opportunities

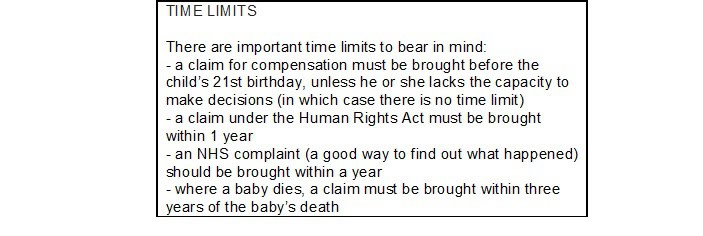

Where opportunities to prevent and treat GBS are missed because of a failure by a person or organisation to meet their responsibility to care for another person, the person injured as a result can claim compensation. Missed opportunities can arise in a number of different ways.

One of the most common failures is the failure to offer preventative antibiotics (IAP) to the mother despite the presence of the risk factors mentioned above, even if the mother is known to carry GBS. Another common failure is to delay in providing IAP. Failing to spot the significance of signs of infection, failing to follow protocols, guidelines and procedures, which if spotted or followed would have led to preventative antibiotic treatment are all common reasons for bringing a claim if the baby suffers harm as a result.

If the baby shows signs of infection but these are not picked up on or their significance is not recognised, the opportunity to start treatment is missed or delayed with potentially catastrophic consequences.

Other failures that can lead to missed opportunities can include: failing to keep proper records, failing to advise of risks, failing to offer GBS testing if the mother is known to have previously carried GBS.

What did I learn?

In short, I’m not convinced by the arguments against testing, I find the GBSS website and information provided there in support of GBS testing persuasive, and I hope the GBS3 trial will provide clear evidence in support of steps that will eradicate GBS infections in babies and the need for people like BZE to bring claims for compensation for their devastating injuries.

I won’t hold my breath though. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the GBS3 trial set up has been delayed. It is now to start this Spring 2021. I may need to wait until next year’s Groundhog Day.