Are Midwife-Led Birth Centres (MLBCs) safe?

The upsetting BBC Panorama episode that aired on 29 January 2024 described the tragic, avoidable deaths of two babies: Jasper White and Margot Bowtell, who died after complications during delivery at Cheltenham (Aveta) Birth Centre.

The episode focussed on maternity services at Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Inevitably, it also raised fears about the safety in the UK of Midwife-Led Birth Centres (MLBCs).

What happened?

The midwives who delivered Jasper in July 2019 appeared unconcerned by a deterioration in his health. They then delayed acting on his need for urgent medical attention. The Healthcare Safety Investigations Branch (HSIB) found that there was a 50-minute delay in transferring him to the neonatal unit in Gloucester Royal Hospital. He died just 11 hours after being born.

The same two midwives were helping Margot’s mother in May 2020. The HSIB found that they ignored episodes of bleeding during the night, at which point they should have transferred her to the obstetrics unit at Gloucester Royal Hospital. When Margo was born some hours later, she was not breathing. She had to be rushed to the neonatal unit at Gloucester and then to Bristol. She died three days later.

A complication during labour or shortly after birth can, if not recognised and acted on immediately, lead to the baby being deprived of oxygen. If the baby’s brain does not receive enough oxygen and/or blood flow around the time of birth, often referred to as ‘asphyxia’, ‘birth asphyxia’ or ‘perinatal asphyxia’, it can cause long-term disability and even death. Lifelong problems after a hypoxic injury can include cerebral palsy, problems with eyesight and hearing, learning or behavioural difficulties and epilepsy. The impact on families is immense.

It is generally accepted that a baby’s brain can withstand up to 10 minutes without oxygen. After that, irreversible damage starts to occur. If completely starved of oxygen for 25 minutes, the baby will not survive.

So, every second really does count when the mother or baby get into difficulty.

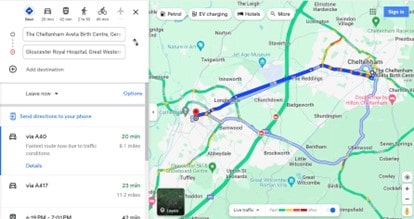

Cheltenham (Aveta) Birth Centre was a free-standing, or “stand alone” midwife-led unit. It was within Cheltenham General Hospital, to which women needing an epidural for pain relief during labour could be transferred. However, the main obstetric and neonatal units needed in case of complications were at Gloucester Royal Hospital 8.1 miles away.

Even if blue-lighted, the journey time of around 20 minutes,would be a cause for concern for a mother or baby in difficulty. Any delay on top of this transfer time is bound to be critical. The added delays by the midwives in arranging transfer of Jasper and their failure to transfer Margot’s mother when called for, had heartbreakingly tragic consequences.

Cheltenham (Aveta) Birth Centre

As is common with midwife-led birth centres (MLBCS), Cheltenham (Aveta) Birth Centre was equipped for normal deliveries without complications. It was unapologetically designed to “make the journey into parenthood as smooth as possible,” with “tools to promote a natural delivery”, including birthing pools, birthing balls, cushion, low lighting, aromatherapy and music.

The Care Quality Commission last inspected it in 2015, when it rated the maternity services at Cheltenham “good”. One of the criteria for measuring success at the centre, and presumably at other MLBCs, at that time appears to have been the rate of transfers from the centre to obstetric units: “Transfer rates of approximately 22–25% were reported from midwife-led units into the obstetric unit, slightly below (better than) the Birthplace survey findings of 26.4%.”

If a low transfer rate from the MLBC to an obstetric unit was a measure of its success, one must wonder whether this influenced the approach of midwives involved in the care of Jasper and Margot’s mother. How pressured were they, consciously or subconsciously, to resist a decision to transfer to keep the centre’s “good” rating? Or did the emphasis on “natural delivery” lead to a false sense of security?

One must also ask what role that CQC 2015 “good” rating played in the minds of hospital management years later. The whistleblower at Cheltenham, midwife Michelle, drew attention of hospital management to the inactions of the two midwives following Jasper’s death in 2019 and again in 2020 following Margot’s death. No steps were taken to review what had happened and learn from mistakes. Could there have been an over-reliance by management on a rating that was by then four/five years out of date? Could they have dismissed the whistleblower’s concerns because they challenged the CQC rating?

Education, resources, infrastructure and collaboration are key

Many countries have implemented midwife-led care by setting up birthing centres. These centres can be within, or next to, a hospital, or can be freestanding. There is evidence that midwife-led birthing centres (MLBCs) are a safe birth setting for healthy pregnant women, if midwives have up to date training and adequate resources and infrastructure are available.

In the UK, the resources and infrastructure are anything but adequate.

The UK has faced a significant shortage of midwives since well before 2010. There is currently a shortage of about 2,500. Some trusts have more than one in five midwife jobs unfilled. Maternity units are struggling over safety concerns. The calls for something to be done grow louder.

Both the Health and Social Care Select Committee on maternity safety and the Ockenden report into maternity services at Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust recommended Government action to increase the maternity workforce in order to delivery safer maternity care.

The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) has called for urgent Government action to end the longstanding and chronic midwifery shortages in England. The RCM’s call comes as the All-Party Parliamentary Groups on Baby Loss and on Maternity push for urgent action on the maternity staffing crisis.

One of the consequences of the midwife shortage is lack of experience, education, and training. All of these contribute to an unsafe MLBC and may have contributed to the unacceptable risks taken by the midwives at Cheltenham.

Another key element of a safe and effective MLBC is well-functioning collaboration across all levels of service. This requires effective consultation and referral networks so that if women or newborn babies do develop complications, easy access to the next level of care is available. This approach is known as a Network of Care (NOC).

This element cannot exist in an NHS where the lack of resources and infrastructure is not limited to maternity services. The first report of the BMJ Commission on the Future of the NHS, just published, goes as far as to call for the declaration of a national health and care emergency and an urgent reset for the NHS as a whole.

The effectiveness of MLBCs depends on multiple interlinked factors, not least of which is resources, in terms of staffing and funding levels, staff training and education, but also management, communications and culture. It is hard to have confidence in any MLBC’s effectiveness when it is trying to function in a health service “in crisis and stretched beyond breaking point”.

Tellingly, Cheltenham (Aveta) Birth Centre closed for labour in October 2023 and is now open for antenatal appointments only. In the meantime, the CQC is reviewing the quality of care at Cheltenham General Hospital, as part of checks on locations registered by Gloucester Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

If you are concerned about the care you or a loved one received at a Midwife-Led Birthing Centre, please do get in touch with our Child Brain Injury team for advice. We will help if we can.