In 2019, the Prime Minister created a new Office for Veterans Affairs. The Office was intended to provide lifelong support to military personnel, including after they had left the service[1]. It marked the first time that veterans’ interests and needs would be overseen by a dedicated ministerial team and followed the first ever UK-wide “Strategy for our Veterans”, published jointly by the UK, Scottish and Welsh Governments in 2018[2]. The Strategy was created in consultation with veterans’ charities, local authorities, academics, volunteer groups, members of the public sector and private companies.

If there’s one thing these activities make clear, it’s that a coordinated, cooperative effort will always be required if we are to provide the most effective and comprehensive support to any demographic. To that effect, Bolt Burdon Kemp, in partnership with military charity Veteran’s Lifeline, have created the 2020 Military Charity Barometer. It’s an open survey directed at military charities, with our aim being to seek a consensus viewpoint from the charities that are on the frontline of providing support for military personnel. As solicitors with years of experience handling military claims, we see first-hand the devastating impact that a lack of appropriate support or overview can have on those who serve.

Here are the main findings from the survey so far, based on 20 responses:

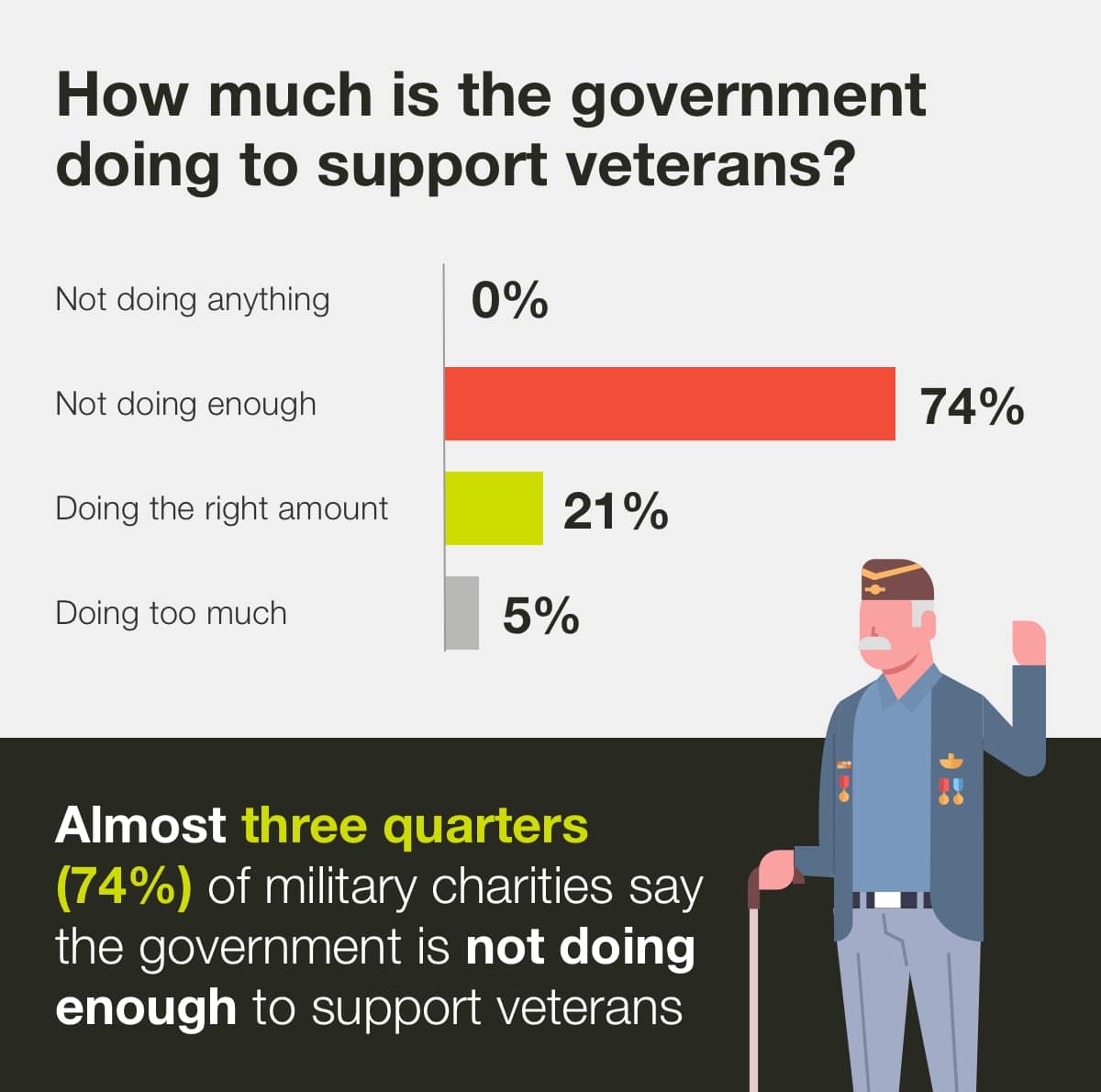

Military charities say the government isn’t doing enough to support veterans

Any type of transition from one type of work to another will require adjustment. Similarly, the transition back to civilian life after being in the military often brings with it a period of adjustment within which a service leaver will need to address issues relating to accommodation, finances, education, work arrangements, healthcare, mental health, and more. So, how well are we supporting service leavers during this period of change?

Almost three quarters (74%) of the military charities we surveyed stated that they believe the government is not doing enough to support veterans. In fact, only 21% would agree that the government is doing the right amount when it comes to their efforts in supporting veterans with the wide spectrum of issues they may face when leaving service.

Introduced in 2000, the Armed Forces Covenant (AFC) has been one way the government has attempted to solidify their commitment to supporting service leavers. Twenty years on, it’s clear the AFC pledge itself hasn’t been enough to satisfy those on the frontline of veteran support that the government is supporting service leavers properly.

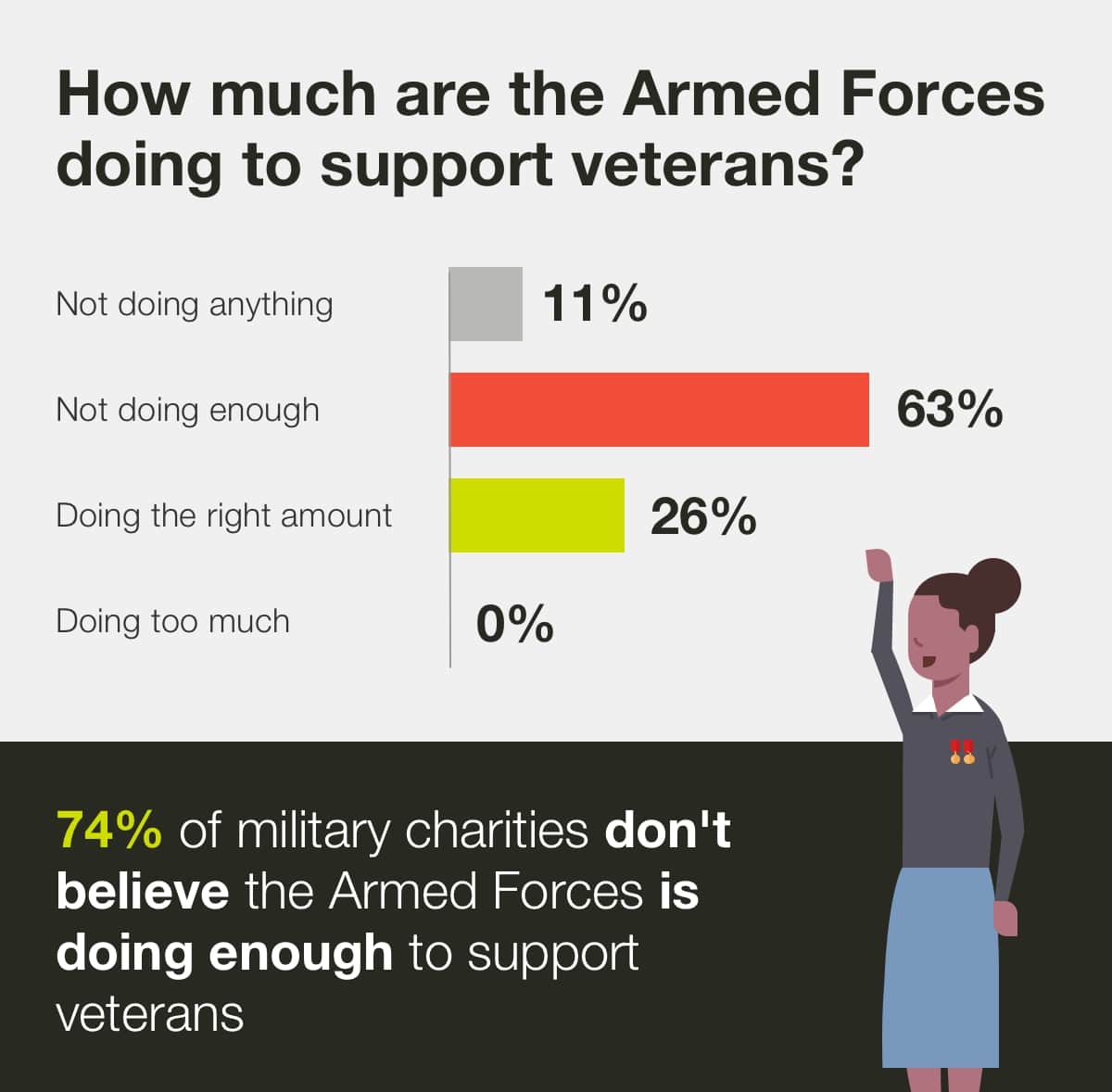

Military charities are similarly united in their stance against the Armed Forces. Over three in five (63%) believe the Armed Forces needs to do more to support veterans, with only a quarter (26%) stating that they believe the Forces are doing the right amount. Crucially, one in ten (11%) military charities believe the Armed Forces isn’t doing anything to support veterans; a damning verdict that demonstrates much of the frustration around the procedures (or lack thereof) in place for service leavers.

Nicholas Perry from Veterans Lifeline suggests “the government could instruct the Ministry of Defence (MOD) to maintain some level of contact with veterans post-discharge. At present,” he notes, “service leavers receive an email from the MOD twelve months after discharge from service. The email basically says, ‘we hope everything is going well and if not, here are some organisations that may be able to help you’. This isn’t nearly enough.”

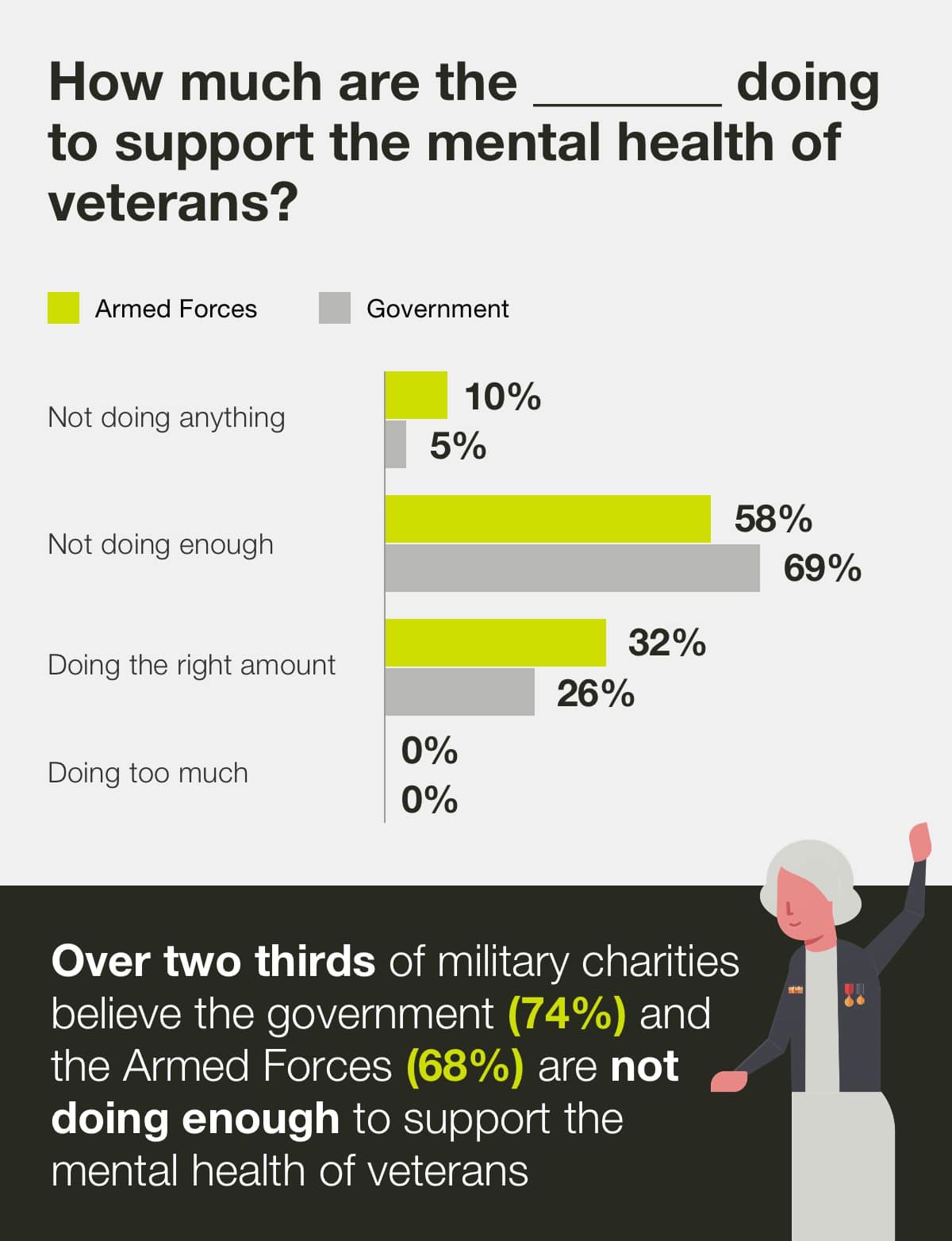

Military charities highlight a lack of support for veterans’ mental health

The latest UK Armed Forces Mental Health report[3] showed that 2.7% of UK Armed Forces personnel were assessed with a mental health disorder by the MOD Specialist Mental Health Services. Servicewomen were more likely to have a mental health diagnosis than servicemen, while 20 to 44-year olds were the biggest age demographic to present with a mental disorder. The same report found that rates of PTSD were low, making up 7% of all mental disorders assessed at the MOD Specialist Mental Health Services and affecting only 0.2% of all military personnel.

However, I’d argue that these figures may be misleading. It doesn’t take into account the veteran community, which makes up many millions of people. PTSD does not always manifest in the immediate aftermath of trauma and sometimes it can take months or even years before the condition surfaces and symptoms become debilitating. I also sympathise with those personnel who suffer with symptoms but choose not to report to their Medical Officer, sometimes out of fear of what it may mean for their careers, income and families. In a glaring omission, those who have suffered after leaving the service are not included in these official statistics.

It’s no wonder, then, that over two thirds of military charities say they don’t believe either the government (74%) or the Armed Forces (68%) are doing enough to help support the mental health of veterans. Through our survey, military charities also reported that they take it upon themselves to pick up the slack, potentially to the detriment of other work they could be doing. One in five (21%) military charities believe that the charity sector is doing more than they need to when it comes to supporting ex-service personnel with their emotional and psychological wellbeing.

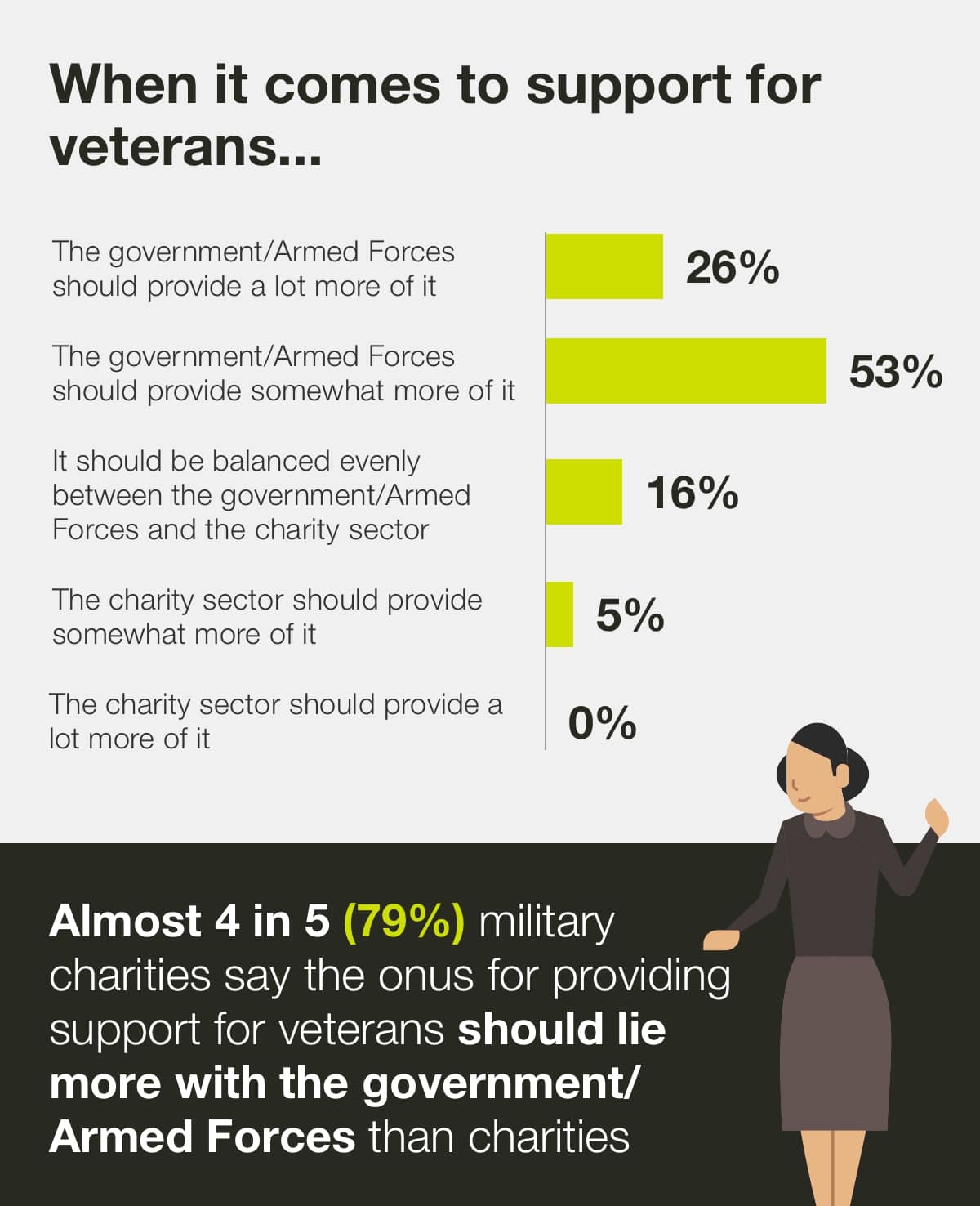

In light of this, it’s unsurprising that almost 4 in 5 (79%) military charities say the onus for providing support should lie more with the government than with the charity sector. In contrast, only 16% of military charities believe support for veterans should be balanced evenly between the government/Armed Forces and the charity sector. It’s a rallying call that neither the government nor the MOD should ignore.

Military charities call for a closer working relationship with the government

Of course, whatever the issue in question, one thing is certain. By working together, the government, the MOD, the Armed Forces themselves, local councils and military charities can deliver a more effective and efficient support network for our service leavers. While recent efforts have been made to do just this, our survey suggests there’s more to be done.

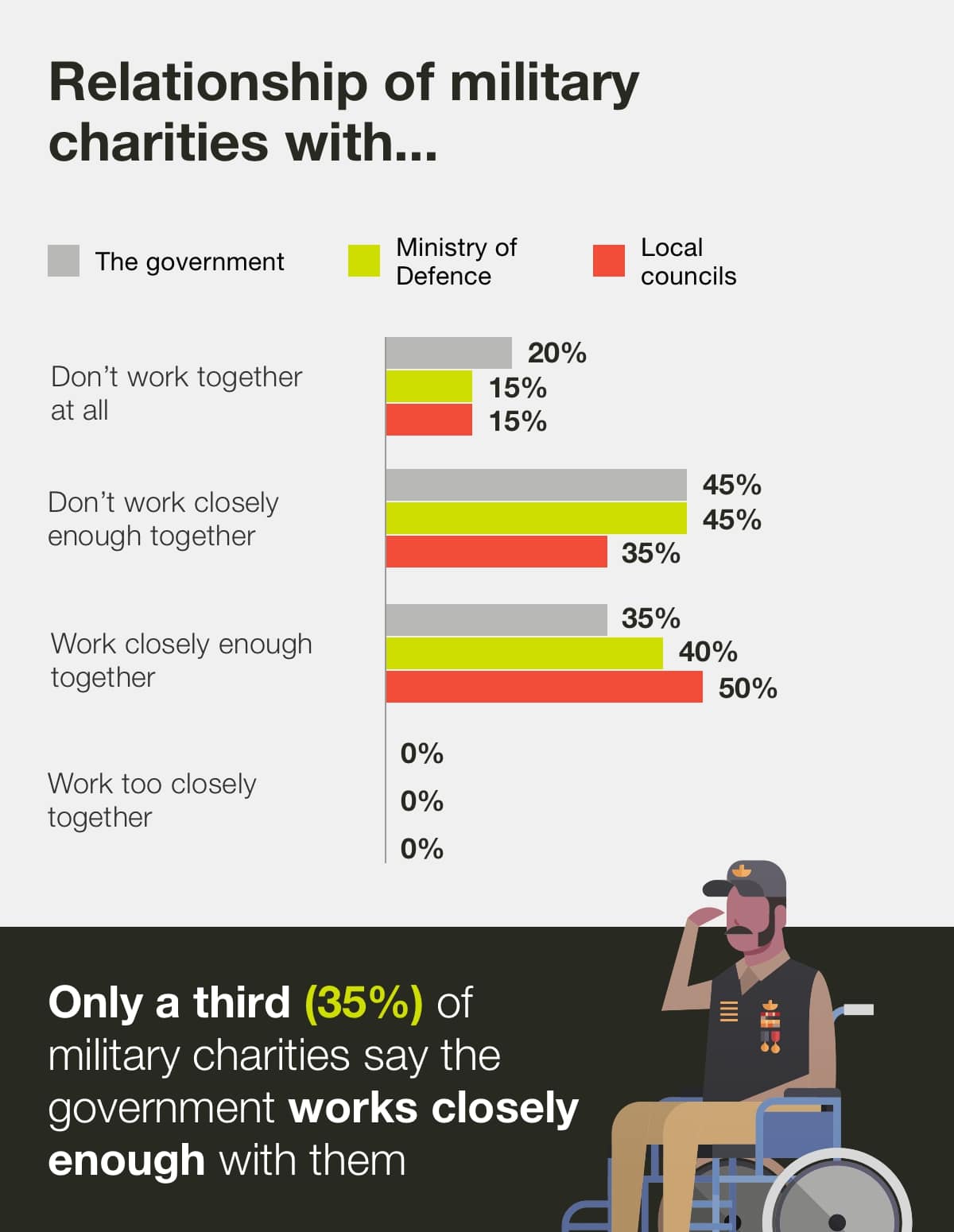

Barely a third (35%) of military charities say the government works closely enough with them, and only 45% of military charities can say the same about the MOD. In contrast, half of military charities are able to say that local councils work closely enough with them. It’s crucial this disconnect is addressed in order to allay any detrimental effect to the support collectively available for service leavers.

The charities we interviewed also called for closer working relationships within the military charity sector. “While there is already excellent cooperation and collaboration between many of the Service charities through Cobseo (the Confederation for Service Charities),” says Robin Bacon of ABF The Soldiers’ Charity, “there are still some military charities operating ‘outside the tent’ and we need to encourage them to work with us ‘inside the tent’ in the best interests of the wider military community.”

Military charities believe the sector needs to undertake better safeguarding

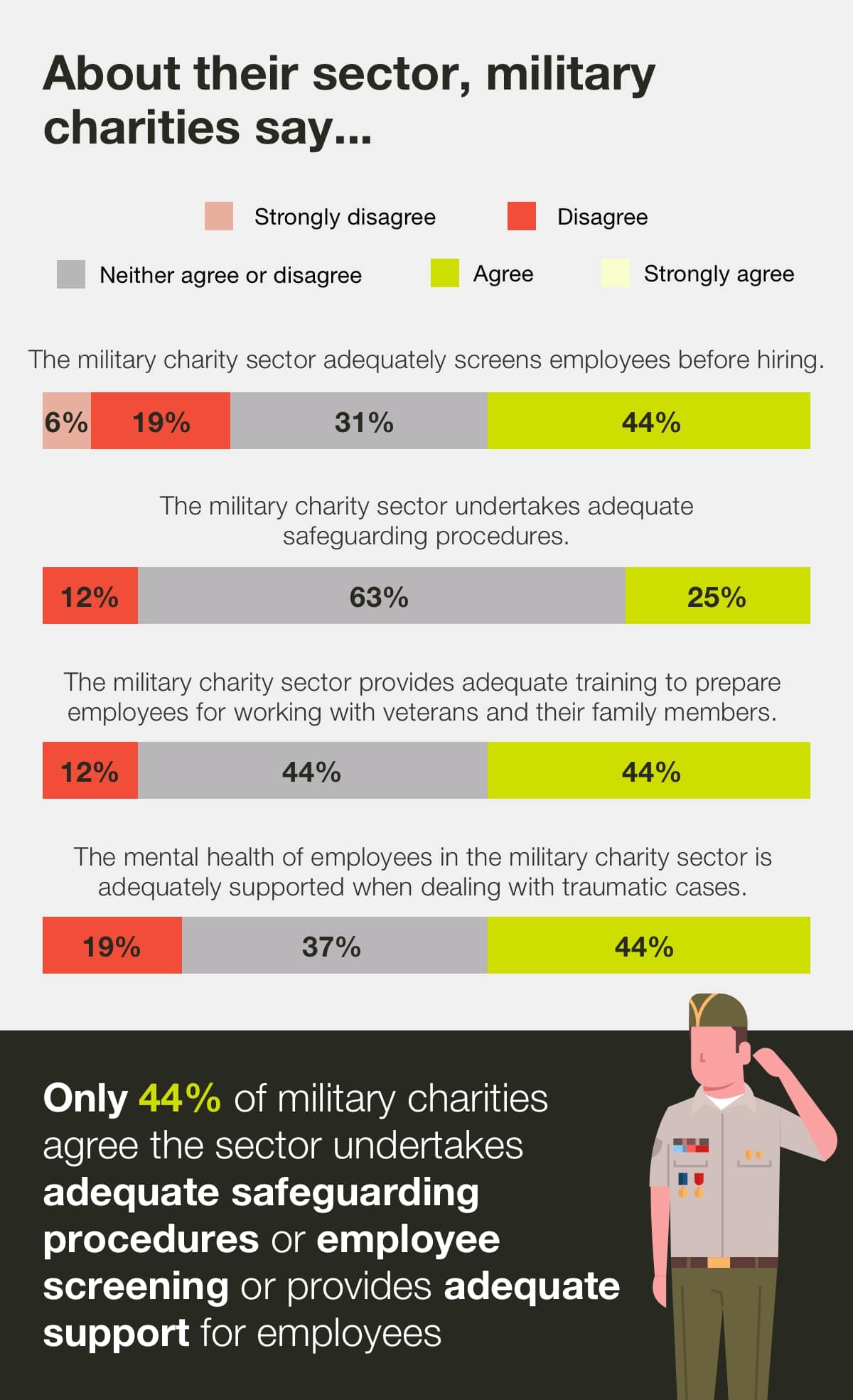

For any military charity, providing proper, holistic support to service leavers should also involve following adequate safeguarding procedures such as those set out by the Charity Commission[4] and making sure employees and volunteers working at the charity are adequately screened. It can also be important to provide training and support for employees, so that they’re qualified to deal both with the cases they encounter and with the aftermath of traumatic cases. In fact, one in five (22%) military charities believe the military charity sector needs more regulation.

Unfortunately, only 44% of military charities can agree that the sector undertakes adequate safeguarding procedures, carries out adequate employee screening or provides adequate mental health support for employees when they need to deal with traumatic cases. And, only 25% of military charities agree that the sector provides adequate training to prepare employees for working with veterans and their family members. Similarly, only 3 in 5 (58%) military charities say they provide formal mental health support or training to staff who deal with traumatic cases.

That said, although less than half of military charities believe the sector adequately screens employees before hiring, three quarters (74%) of the charities report that they themselves do have a strict screening process for hiring employees. This disparity between military charities’ perceptions of the sector and how they self-report is interesting, to say the least.

However, with a more concerted effort by the government, the MOD, the Armed Forces and the military charities themselves – as well as the public and private companies and the local authorities they work alongside with – it’s not impossible to provide balanced, fair and effective support that ensures service leavers – and the charities that assist them – are much better off.

Methodology

The 2020 Military Charity Barometer was distributed via a SurveyMonkey survey, with 20 military charities responding in February-March 2020 to provide their views.

References

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-creates-new-office-for-veterans-affairs-to-provide-lifelong-support-to-military-personnel

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/strategy-for-our-veterans

[3] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/809561/20190620_Annual_Report_18-19_O.pdf

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/regulatory-alert-for-military-charities