Everyone deserves a fair chance at justice. Part of this is having a suitable lawyer to represent you, whether at court or in negotiations. But while everyone deserves proper legal representation at their time of need, not everyone can afford it.

What is legal aid funding?

That’s where legal aid comes in. Legal aid allows you to meet the cost of legal advice or legal representation without having to pay upfront. In England and Wales, the funding for legal aid is provided by the government via the Legal Aid Agency (LAA).

When legal aid was first introduced in 1949[1], it allowed 80% of the British people access to free or affordable legal help. By 2007, government cuts meant only 27% of the population would be eligible for legal aid[2]. In 2013, austerity measures saw the government introduce further cuts via the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO).

It severely limited the eligibility criteria for qualifying for legal aid, and caused widespread issues. This included the loss of jobs in this area of law leading to a lack of legal aid providers (creating ‘legal advice deserts’ in some areas of the country), culminating in situations such as parents being unable to afford legal representation in family court for custody cases. [3]

Read our latest research for some facts and trends around the legal aid funding scheme.

The most deprived areas of the UK need the most legal aid

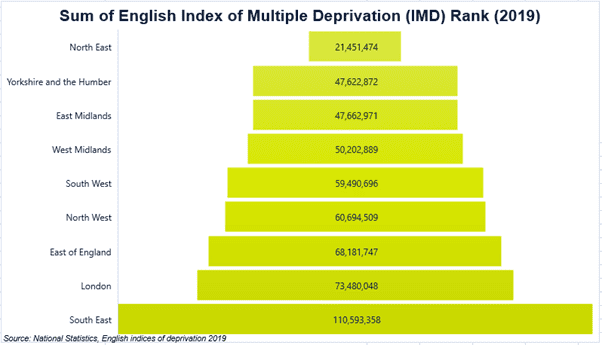

The English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) ranks small, local areas in England by several measures of deprivation. Looking at factors such as income and employment deprivation, education and skills, health, crime and barriers to housing, the IMD gives each local area a score called an Index of Multiple Deprivation Rank. The lower the score, the more deprived the area is deemed to be.

According to estimates from the 2019 IMD Ranks, the most deprived regions in England are the North East, Yorkshire and the Humber and the East Midlands. This is based on the sum of the IMD Rank for each region, which is shown in the diagram below.

While the IMD rank is more accurate on a local, rather than regional level, it serves as a useful point from which to compare the regional data provided by the government on legal aid funding.

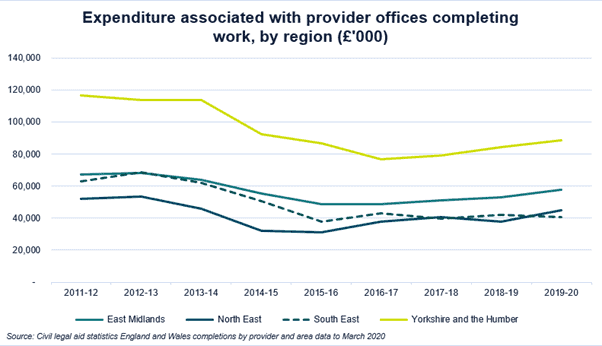

For example, government data on the location of provider offices – i.e. the organisations providing legal assistance to clients via legal aid funding – shows that one of the most deprived regions of England also has the highest legal aid expenditure.

With the exception of London (thanks to its high number of provider offices (660 in 2019-2020 compared to an average of 204 across all regions excluding London), Yorkshire and the Humber have consistently recorded the highest expenditure when it comes to legal aid funding. The difference is particularly evident when compared to the South East – the area with the least amount of deprivation – but Yorkshire and the Humber also has a higher expenditure than areas with high rates of deprivation, such as the North East and the East Midlands.

The full table of all regions is below:

| Expenditure associated with provider offices completing work, by region (£’000) | |||||||||

| 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | |

| London | 268882.8 | 270514 | 256927.5 | 247722.6 | 217175.1 | 225846.5 | 225183.9 | 234427.6 | 231784 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 116782.2 | 113910.6 | 113952.9 | 92245.4 | 86866.44 | 76850.23 | 78977.17 | 84115.38 | 88459.13 |

| North West | 114272 | 119712.6 | 118795.7 | 98648.01 | 85460.47 | 76911.89 | 82160.78 | 81811.6 | 87953.73 |

| West Midlands | 90169.08 | 94320.04 | 93741.96 | 81903.54 | 75410.95 | 74118.12 | 72371.29 | 75390.38 | 83443.32 |

| South West | 87200.82 | 89616.36 | 86136.83 | 77689.58 | 65429.78 | 63911.77 | 67276.01 | 63718.81 | 66812.38 |

| East Midlands | 67437.54 | 68063.1 | 64089.53 | 55349.47 | 48827.81 | 48933.57 | 51071.37 | 52893.88 | 57915.02 |

| South | 57183.23 | 52257.93 | 54967.38 | 48836.07 | 45336.6 | 43228.27 | 48797.32 | 50170.53 | 54223.97 |

| Eastern | 71659.58 | 74311.01 | 69161.39 | 58752.22 | 48659.82 | 46020.73 | 47053.11 | 49861.2 | 50505.17 |

| Wales | 63733.23 | 66590.42 | 66308.67 | 54680.62 | 39191.12 | 40697.29 | 43269.21 | 43032.8 | 46100.69 |

| North East | 52072.95 | 53402.81 | 45664.37 | 32243.37 | 31321.66 | 37994.57 | 40584.4 | 37668.64 | 45008 |

| South East | 62850.72 | 68652.39 | 61771.59 | 50725.35 | 37705.15 | 43001.05 | 39721.56 | 41912.46 | 40451.35 |

| Merseyside | 39903.92 | 40400.56 | 39971.99 | 35064.93 | 31312.89 | 30121.93 | 30181.71 | 30677.4 | 35047.51 |

The number of legal aid providers has fallen over the years

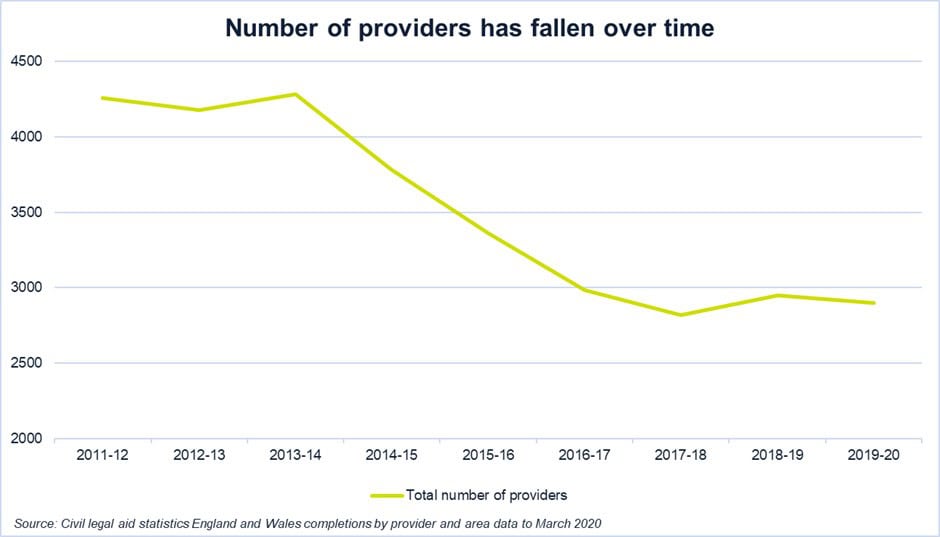

Looking generally into the civil legal aid landscape in England and Wales, there’s been a steady drop in the number of legal aid providers over the years.

In 2011-12, the total number of providers stood at 4,257. Between 2013 and 2018, this dropped by 34%, following significant changes to civil legal aid in England and Wales. In 2016, the UK government stated that they couldn’t conclude that this has resulted in people facing difficulties in obtaining help with legal problems.[4] However, with sweeping cuts across many areas within legal aid, and newer investigations suggesting law centres are massively struggling[5], the government’s conclusion was likely optimistic.

Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) clients make up the majority of legal aid claimants

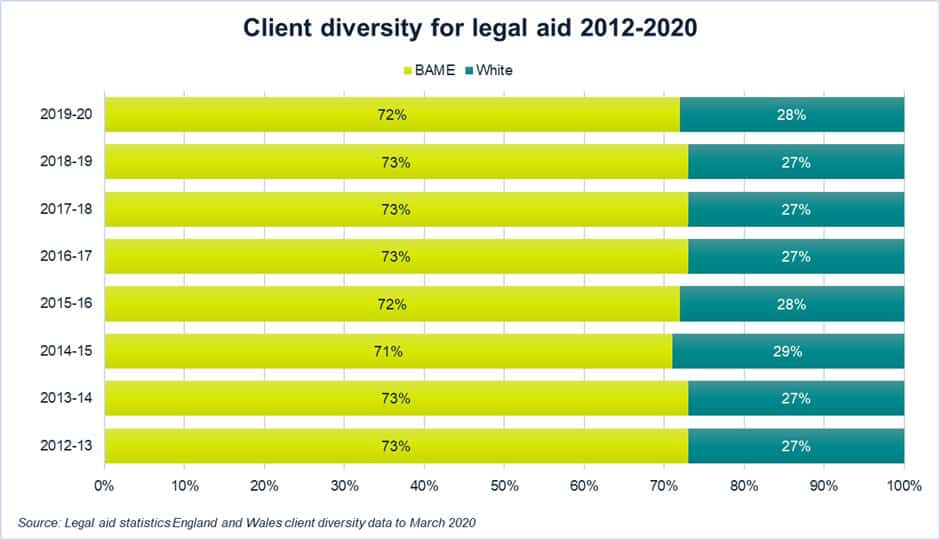

Another worrying factor within the demographics of those who receive legal aid is that Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups are the most likely to make use of legal aid, as the government’s own legal aid client diversity data shows.

The following table accounts for all civil and criminal legal aid cases where ethnicity is known (i.e. not listed as unknown or suppressed). The figures are represented as a percentage of the total number of clients where ethnicity is listed as either BAME or white:

Since 2012-13, the ethnicity split when it comes to legal aid clients has remained fairly consistent, with people from BAME backgrounds making up 71-73% of criminal and civil legal aid cases in England and Wales.

This suggests that, if legal aid funding continues to be cut, Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups are most likely to be affected. What’s more, one of the main areas of previous cuts was social welfare law – an area which people on low incomes and disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to need legal help with. When you consider that BAME groups in the UK are more likely to have low incomes[6], it’s possible that BAME groups will be the most affected by any further cuts to legal aid.

The British public don’t believe civil justice is accessible nor affordable

To put all this into wider context, the last time the legal aid system was reformed was 9 years ago (2012), and the legal aid funding system – which determines who gets access to legal aid – was last assessed a decade ago (2011).

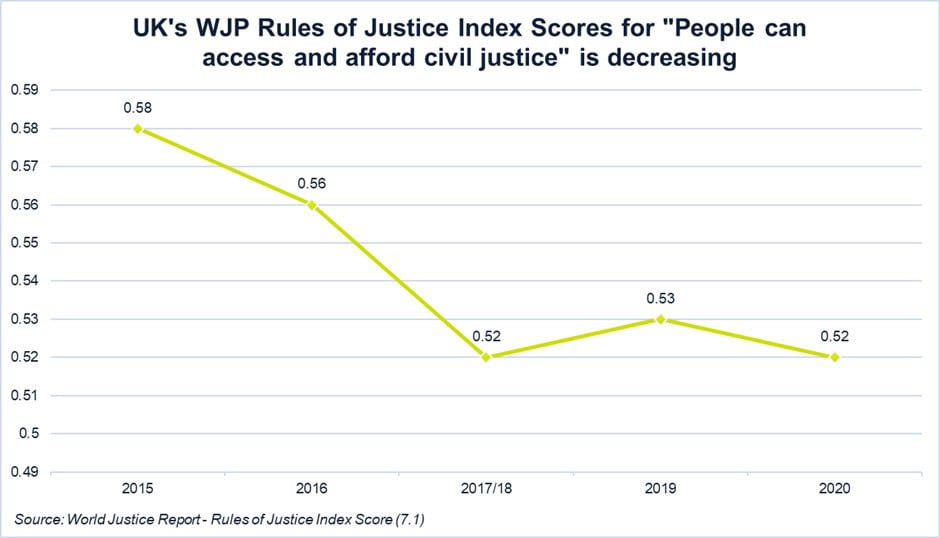

While the system remains stalled, public perception is evolving – for the worse. In the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, the UK currently ranks 17th in the world for the public perception of civil justice in the country – from a high of 13th overall in 2015. Access to and affordability of civil justice was the lowest scoring factor within the section, and low public scores have meant it’s steadily dropped in the rankings from 2015 to 2020.

In 2015, the British public’s responses to the statement “People can access and afford civil justice” meant the UK got an index score of 0.58 (with 1 being the highest possible score). In 2016, this dropped to 0.56, and it had further fallen to 0.52 by 2020. This meant the UK placed a lowly 79th out of 128 countries for this specific factor in 2020 (in comparison to 31st out of 102 countries in 2015).

How to apply for legal aid funding

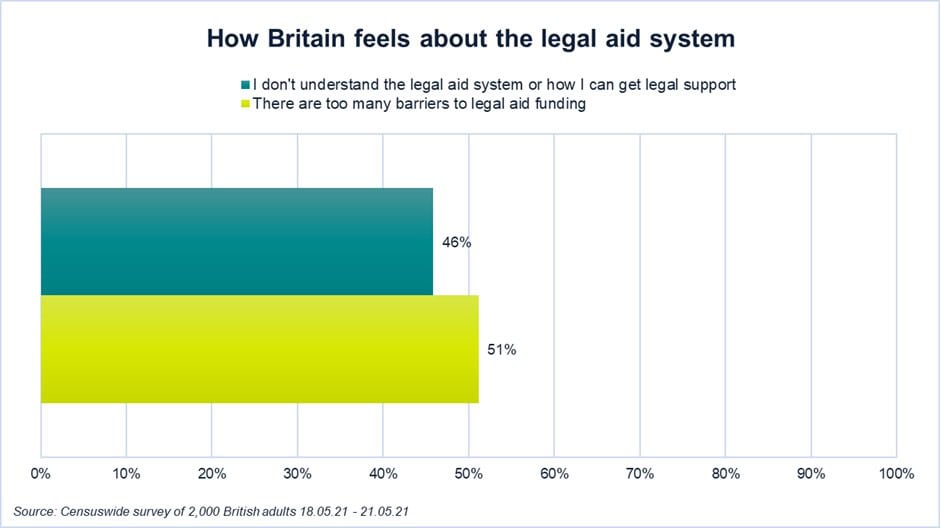

Part of the reason for this may be explained by findings from our own survey. We asked 2,000 respondents from England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland whether they understood the legal aid system or how they can get legal support. 46% of respondents stated that they didn’t. Half of the respondents also stated that they believe there are too many barriers to legal aid funding.

If this sounds like you, our short guide below on how to apply for legal aid funding may help:

- Legal aid is provided for all criminal cases except minor offences.

- In civil cases, legal aid can be used to meet the costs of legal advice if you’re facing a serious problem such as risk of losing your home, domestic violence, discrimination, asylum or immigration issues, welfare benefits, or inquests.

- You’ll need to show evidence that you’re unable to meet the costs of legal help yourself. In the current system, this means having less than £8,000 in capital assets (money, interest or land that you or your partner possess), and earning less than £2,657 per month with less than £733 in disposal income.

- If you qualify based on the above, you can speak to a specialist at the Civil Legal Advice (CLA) helpline, set up for specific legal aid problems in England and Wales. From there, a specialist will help determine if your application can progress.

- Alternatively, you can contact a legal aid adviser at no cost to you, who can make the legal aid application for you. You may need to pay an amount towards your legal aid yourself from your own income.

- There are also other avenues to get free legal help, from contacting your local Citizen’s Advice, getting advice from a solicitor at a law centre, applying for help from a volunteer barrister through Advocate, or using a free law advice clinic via LawWorks.

- Another option is very specific to certain types of cases. If you have a personal injury claim or a medical negligence claim, some law firms provide their services on a ‘no win no fee’ basis, where your solicitor only gets paid if they win your case. Get more information on this in our article on the topic.

In our time of need, getting legal support can help us get the justice we deserve. With government cuts continuing to reduce access to legal help, it’s likely an increasing number of people are left unable to access the resources to have their voices heard and their needs met properly. We need to reassess the legal aid system to ensure it’s fit for purpose and can serve everyone fairly.

[1] https://www.jstor.org/stable/25722164

[2] https://www.legalcheek.com/lc-journal-posts/a-brief-history-of-legal-aid/

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/law/2018/dec/26/legal-aid-how-has-it-changed-in-70-years

[4] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn06645/

[5] https://committees.parliament.uk/work/531/the-future-of-legal-aid/

[6] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/income-inequality-by-ethnic-group/