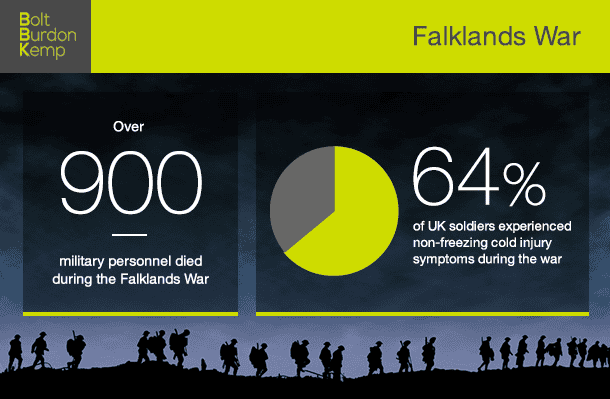

On 2nd April 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, kick-starting a bitter ten-week war with Britain. More than 900 British and Argentinian servicemen lost their lives during the conflict and hundreds were left severely injured. As we mark the 35th anniversary of the war, it’s hard to believe that one of the biggest causes of non-combat related casualties was the cold. We explore the true extent of cold injuries both then and now, and ask why the Ministry of Defence (MoD) isn’t doing more to protect vulnerable soldiers.

A muddy British war

The Falkland Islands are located in the South Atlantic Ocean, and have a particularly wet, cold and windy climate. This made it difficult terrain for British troops to navigate when they first landed on the archipelago in ‘82. During the campaign to take back the small UK colony, British soldiers had to wade through boggy wetland, causing a huge number of cold injuries. A survey of armed forces personnel who served in the war found that 64% of soldiers in infantry units had experienced symptoms of non-freezing cold injuries.1 These injuries had a lasting impact on their careers and family life.

More than a common cold

Non-freezing cold injuries usually happen in the outdoors, when people are exposed to cold and wet conditions for a prolonged length of time. Known as ‘trench foot’ during World War I, the condition affects the hands and feet, and sometimes the genitals. NFCIs, as they’re commonly called, can cause chronic pain, numbness and swelling in the parts of the body affected, and can permanently affect a person’s ability to use their hands and feet. It’s also more common in those of Black African and Black Caribbean descent. With no cure available, painkillers are the only source of temporary relief for soldiers with the condition.

Easily preventable?

Are cold injuries just another peril of war, like the loss of a hand or a limb? The short answer is no. The injuries are entirely preventable and the MoD has its own guidance on how to reduce cold injuries during outdoor exercises. This includes simple steps such as:

- Providing the right cold weather equipment, shelter and clothing

- Immediately referring those with symptoms to a medical officer

- Monitoring weather conditions, temperatures, and cancelling exercises when risks are increased

- Training all service personnel and particularly officers who organise outdoor exercises

But instead of following the guidance, soldiers are often told to ignore the problem and ‘man up’, which usually just makes the symptoms worse. Ahmed Al-Nahhas, a partner in Bolt Burdon Kemp’s military team, commented:

“NFCIs are caused by and become worse with prolonged exposure to the cold. Soldiers are generally tough and don’t complain, particularly when on promotional courses which may be crucial to their career development. When they do complain; their superiors need to listen. Even the MoD’s own guidance and medical experts recommend immediate evacuation from the field once NFCI symptoms are identified. Without good communication and immediate action, what can start as a mild reaction to the cold can become something debilitating and incurable.”

The sobering stats

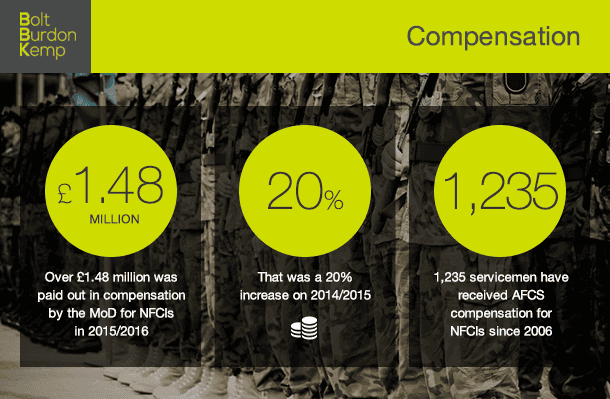

More than three decades on from the Falklands War, it’s shocking that cold injuries are still a major problem in the UK armed forces – despite being entirely preventable. In 2015/2016, the government paid out over £1.48 million2 to servicemen for non-freezing cold injuries under the Armed Forces Compensation Scheme – a 20% rise on the previous year.3 Since 2006, 1,235 armed forces personnel have received compensation from the government for the injury.4 And the number of veterans claiming compensation for the injuries has gone up too. Last year saw a 16.7% rise in the total number of service personnel awarded compensation for cold injuries under the Armed Forces Compensation Scheme.5 It’s clear that the problem is not going away.

The impact on career, family and work

For soldiers who fought in the Falklands War and those who serve today, the long-term effects of NFCIs can be devastating. Soldiers are almost always medically downgraded or discharged from duty as they can no longer take part in outdoor activities due to the loss of feeling in their hands. The nature of the injury means most servicemen can no longer work in the outdoors. And the effects are often mental as well as physical. Many go on to develop depression and anxiety because of the impact of the injury on their career and family lives.

The impact on ethnic minorities

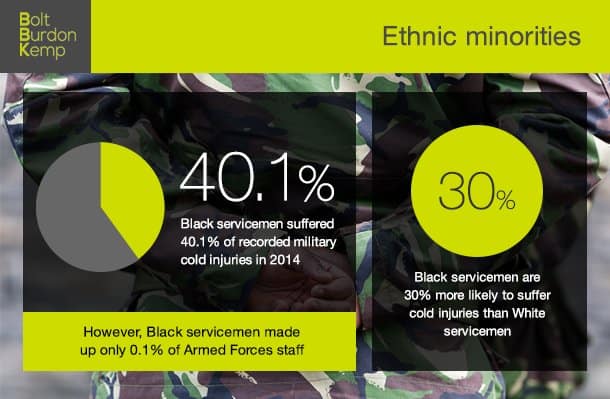

Jacob Anum and Abdoulie Jallow are both veterans who suffered cold injuries during routine military training courses. Anum experienced a moderate NFCI in his hands and feet while serving in Germany, while Jallow was injured by the freezing conditions he slept in one night on duty. What Jacob and Abdoulie also have common is they’re both veterans of African descent. Black soldiers are 30% more likely6 to suffer cold injuries than their Caucasian counterparts. Data obtained from a Freedom of Information request shows that Black servicemen suffered 40.1% of recorded cold injuries in the army, in 2014.7 This percentage is startling when you consider Black servicemen only make up 0.1% of UK armed forces staff.8 The Ministry of Defence is not just failing its soldiers. It’s failing our Commonwealth soldiers particularly badly.

Options for injured soldiers

For veterans like Jacob and Abdoulie, who’ve sustained a life-changing cold injury, compensation from the government is available. The MoD provides compensation through the Armed Forces Compensation Scheme, but pay-outs are usually small and don’t address the long-term implications of the condition. Most veterans find that suing the MoD through the Civil Court is the only way to get the amount they really deserve due to their loss of earnings and the impact on their life and career. Although these larger amounts of compensation will never ease the physical pain, they are a step in the right direction, and can help soldiers rebuild their lives again.

I am a Partner at Bolt Burdon Kemp specialising in military claims. If you suffered an injury while in the armed forces, you may be entitled to claim compensation. Get in touch with our team of specialist military claims lawyers to discuss your case and find out if we can help you make a claim. You can contact me free of charge and in confidence at ahmedal-nahhas@boltburdonkemp.co.uk or on 020 7288 4818. Alternatively, you can complete this form and one of the solicitors in the team will contact you. Confused about the claims process? We’ve created a simple flowchart to help you understand the key steps in both an AFCS and civil claim process.

References

1 https://extremephysiolmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2046-7648-2-23

2 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/…./attachment_data/file/560011/FOI2016-08230_redacted.pdf

3 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/…./attachment_data/file/560011/FOI2016-08230_redacted.pdf

4 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/…./attachment_data/file/560011/FOI2016-08230_redacted.pdf

5 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/…./attachment_data/file/560011/FOI2016-08230_redacted.pdf

6 http://jramc.bmj.com/content/155/1/11

7 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/…./attachment_data/file/482974/PUBLIC_1448967672.pdf

8 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/…./479901/PUBLIC_1447950571_FOI_2015_09245.pdf