Abuse is never okay. There’s no excuse, and yet, when a survivor of sexual abuse goes public with their story, the tide can quickly turn. Too often, instead of listening to and accepting their story (a crucial factor to encourage survivors to disclose the abuse), the public reaction is to vilify them.

‘After all,’ the public seem to think, ‘when a beloved celebrity is accused of sexual crimes, the accuser must surely have a hidden agenda.’ We used a social listening tool and partnered with Lizzy Dening, founder of Survivor Stories, to analyse the public’s response to several high-profile cases of sexual abuse. Read on for our exploration of why society tends to ‘blame the victim’.

Scroll down to read all cases or select the one that interests you from the menu below:

“Facts don’t lie – people do”: the Michael Jackson case

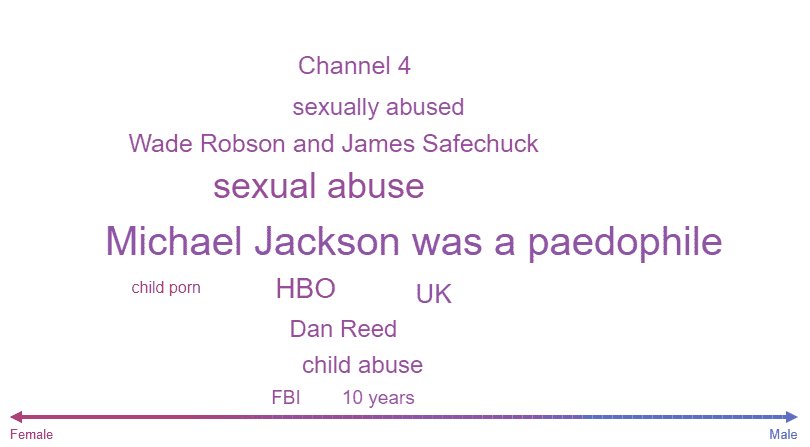

The Leaving Neverland documentary saw Wade Robson and James Safechuck accuse deceased popstar Michael Jackson of historical child sexual abuse. The public reaction was mixed but passionate, with 29,000 people generating 72,000 mentions in a fairly even gender split (47% women, 53% men).

Across genders, the sentiment was more negative than positive, with mentions demonstrating feelings of anger, disgust, sadness and fear. Delving into the reasons why people expressed sadness, we found that many people expressed disappointment at the fact that Michael Jackson was facing accusations rather than sadness about what the survivors had gone through.

This attitude could be due to how rape is covered in the press. Lizzy Dening explains that “one of the problems with the way in which the media reports on rape is that there’s a disproportionate level of coverage around cases of false allegation. Yet, according to estimates from the Crown Prosecution Service, false allegations make up 0.62% of all rape cases.

“In fact,” adds Dening, “a man is more likely to be raped than to be falsely accused of rape.*”

In terms of the words used to discuss the case, women were more likely to use the hashtag ‘#MJInnocent’ as well as mention the accusers by name. In turn, the phrase “Michael Jackson was a paedophile” was used by 51% of men (compared to 49% of women). For a more comprehensive view of the conversation on social media, we also looked at the emojis people used when talking about the case.

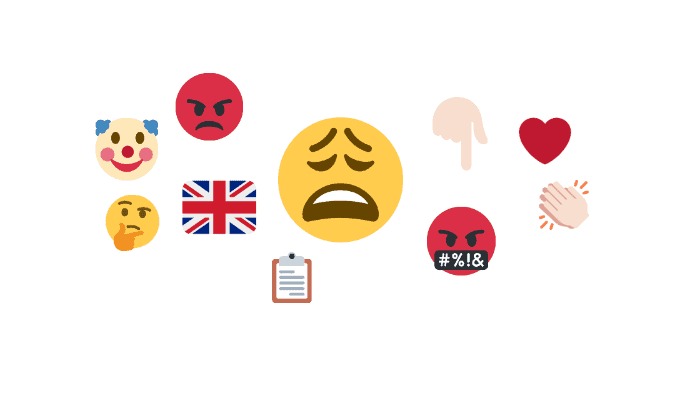

The ‘face with tears of joy’ emoji was the most popular, garnering 790 mentions in total. Interestingly, this represented a mix of sentiments. While many comments made fun of people who still believed in Michael Jackson’s innocence, others made fun of his accusers and attempted to poke holes in their story. For the latter group, the hashtag #FactsDon’tLiePeopleDo also appeared alongside the emoji.

The sentiment that the accusers were lying was also reflected in the popularity of the ‘lying face’ emoji, getting 345 mentions and being often featured alongside the ‘woozy face’ emoji, both times expressing perplexity and disbelief at the accusers’ stories. When it comes to a global star like Michael Jackson, discrediting his accusers was a key outlet for devout fans to continue their idol worship.

Disgust turned to mockery: the Jimmy Savile case

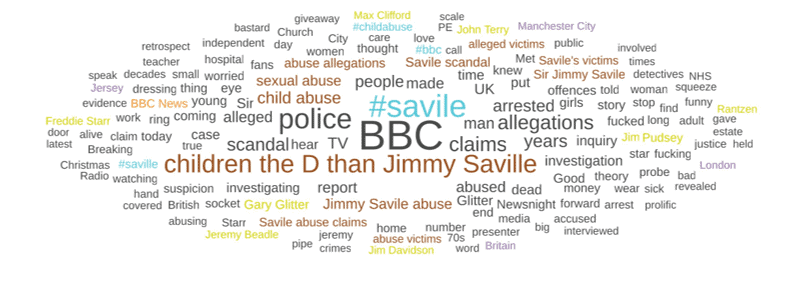

English DJ, radio and television personality Jimmy Savile died in October 2011. After his death, hundreds of adults brought forward allegations that he’d sexually abused them when they were children. As the titular host of children’s show Jim’ll Fix It, Savile had regular access to hundreds of children. Police concluded that Savile had been one of Britain’s most prolific sex offenders, with public reaction initially reflecting this finding.

67,000 people mentioned the case 113,000 times (between 29 Sept 2012 and 29 March 2013, when the case started to be picked up by the media), and primarily expressed disgust (35,818 mentions, representing 56% of posts) and sadness (15,190 mentions (24%)). Disgust was expressed over Savile’s accused crimes, the treatment of the children affected, and the failure to protect the children by organisations such as the BBC and the NHS.

Sadness was expressed by official news sites including the BBC, Sky News and the Guardian regarding the scale of the abuse, with some citing as many as 500 survivors who had come forward. And yet, public sentiment quickly turned sour. With many of the comments being posted during Halloween, comments online included jokes about using Savile’s image to scare kids (for example, dressing up as Jimmy Savile to stop children from trick or treating at their house). As Lizzy Dening states “while dressing as Savile is entirely tasteless, and not at all funny, the intention behind it was – I would hope – to make fun of him, rather than to undermine his victims.”

And yet, mockery was a key theme in the online conversations surrounding this case, with posts using vulgar and suggestive language that made light of child molestation. One such post was “(sic)” with the phrase “the D” being a slang term for male genitalia and suggesting sexual intercourse. It garnered 9,128 mentions mostly through retweets of posts by two since-suspended Twitter accounts. With every mocking post, the experiences of those who had been abused was becoming trivialised.

Dening concedes that perhaps social media is not always the best place to discuss such topics. “Social media is generally a terrible way to have conversations about nuanced and complex issues such as sexual violence,” she explains. “It tends to encourage an atmosphere of animosity and ‘hot takes’ on subjects – where more provocative statements are given more attention.”

Us versus them: the grooming gangs at Rotherham

Britain has seen several stories break of grooming gangs who manipulated and exploited young children for sex and other criminal behaviour. One such case occurred in Rotherham, South Yorkshire, with the story gaining traction online around May 2017 when 19 men and two women were convicted of crimes dating back to the late 1980s.

Online, men were far more likely to talk about the case than women, making up 72% of the 16,000 individual authors. The sentiment was mostly negative with 36,010 mentions across genders (or 95% of posts overall) and 12,690 negative mentions by men alone. Men did express positive sentiment too, with many posters being impressed at the survivors’ composure and bravery.

On the other side of men’s conversation, one popularly re-tweeted post said: “Finally someone has said it, @SarahChampionMP has put the safety of children over political correctness.” The post was referring to Sarah Champion – the Labour MP for Rotherham – who wrote a column in The Sun newspaper stating that “Britain has a problem with British Pakistani men raping and exploiting white girls.”

The divisive article reflected much of the public’s views about the case, with some commonly used words being “gangs” (13,000 mentions), and “Muslims” (10,000). For a more nuanced analysis of conversations on social media, we also looked at the common emojis used. The British flag also made a frequent appearance (250 mentions), as did the ‘swearing, angry face’ emoji.

The phrase “Muslim rape gangs” was also notable and saw 1,682 mentions. Of all cases we investigated, this one expressed significant vitriol against the background, ethnicity and religion of the perpetrators, betraying an “us versus them” mentality from the posters.

“Rotherham is an interesting example of where the media made things worse with good intentions,” says Lizzy Dening. “It’s an issue of disproportionate reporting, and we need some balance. Rotherham was – rightly – a huge story, but all too often stories about child sexual abuse don’t make the news. Just as the media shows that rape looks like ‘a stranger in an alley’, or ‘a young, drunk woman’, it has now shown that child grooming looks like ‘gangs of Asian men and young white girls’. This has a damaging effect on two levels: one, increased racism towards Asian men; and two, making it easier to disguise other forms of abuse and exploitation.”

“Boycott R. Kelly”: gender differences in responses

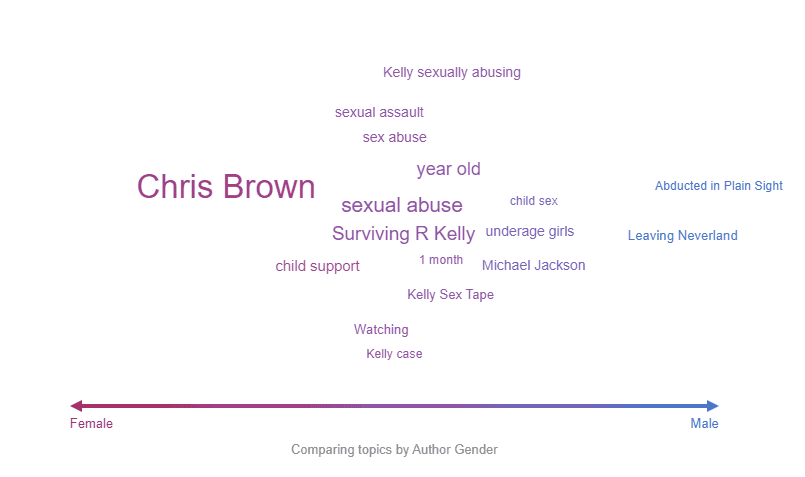

When the six-part docuseries Surviving R. Kelly was released, where several young women alleged rapper R. Kelly had sexually abused them, it saw several prominent pop stars including Lady Gaga and Ciara withdraw their collaborations with the star from streaming services. It also saw 67,000 mentions online, with 32,000 individual authors split into 59% women and 41% men.

Lady Gaga being a survivor of sexual assault herself, Lizzy Dening points out that the popstar also experienced victim blaming: “when Lady Gaga posted about having suffered sexual violence, many of the comments underneath suggested that she’d only come forward as she had an album to promote, or – worse – that she ‘deserved’ it because of some of her stage outfits.

Professor Barbara Gilin notes that people tend to default to victim-blaming thoughts and behaviours as a defence mechanism in the face of bad news. Because, if we can pretend that the victim was targeted because they did something wrong, we can tell ourselves that as long as we do everything right, we can prevent ourselves from becoming a target too.

Dening adds that victim blaming might have an evolutionary basis. “Humans have a pack-animal mentality, and we tend to go along with the dominant ideology rather than wanting to stand out. The dominant ideology in a patriarchal society is that of a male – everything is tailored towards a male viewpoint, especially how we think about sex and power. As survivors often already feel guilt or shame (a normal psychological reaction to trauma) victim blaming compounds that response and makes them less likely to come forward to seek help.

“It would be nice to see a platform responding to that via moderators,” says Dening, “especially as these comments are potentially devastating for other survivors.”

When we analysed conversations about the R. Kelly case, we found the sentiment was mostly negative. There were 30,185 negative mentions, with the top emotions being disgust (23,316 mentions), sadness (7,760) and anger (1,986). Sentiments of disgust ranged from angry reactions to the documentary and R. Kelly’s actions, to posters addressing victim blaming from other posters, to comments that the race of R. Kelly’s targets had allowed him to continue to perpetrate his crimes.

It’s also interesting to see the gender differences in the way the public responded to the case. Most of the conversation online was generated by women, including phrases such as “child pornography” (72% women versus 28% men), “Kelly’s victims” (71% women) and “black girls” (71% women) being used. In contrast, the phrase that was most popular with men was “Quit playing” with 63% of men calling for a boycott of R. Kelly’s music. While women discussed the details of the case, the crimes that were committed and the survivors of the abuse, men, though supportive of the survivors, had a more detached, practical approach.

“Rape a baby”: shocking abuse by Ian Watkins

Ian Watkins, Welsh singer from the Lostprophets, was sentenced to 35 years in prison over child sex offences in 2013, although the news also revealed that allegations of abuse had been made against Watkins as early as 2008. The case saw 13,000 mentions online from 11,000 unique authors, mostly expressing disgust (6593 mentions), sadness (735) and surprise (379).

Mentions of disgust included lamentations over no longer being able to enjoy the music of the Lostprophets, disbelief at the news that he had plotted to rape a one-year old child and shock at hearing the news itself. The mentions also included disgust directed at those who attempted to defend Watkins or make light of the issue through crass jokes.

Much of the conversation online centred around the court case, with the phrase “charged with sexual offences against children” getting 1,715 mentions. Men were most likely to use the phrase “Watkins paedophile,” while women focused on the age of his targets, with the phrases “13-year-old” and “rape a baby”. Similarly, the top emojis used expressed shock, worry and anger.

From the six individual cases investigated, this case saw the least amount of ‘victim blaming’. Lizzy Dening explains that “how the media speaks about sexual violence, and how the rest of us post about it on social media or talk about it in the pub should not be underestimated. I know survivors of rape and abuse who have experienced victim blaming from friends and family – not necessarily with regards to their own cases, but by talking about those in the news.”

“Band of brothers”: the Bob Higgins case

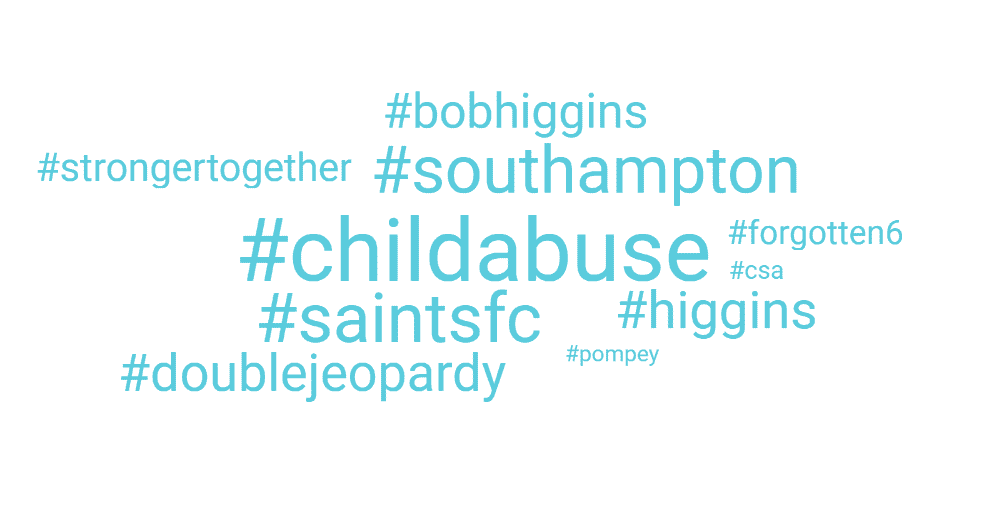

Former Southampton FC coach Bob Higgins was acquitted in 1991 on six counts of indecent assault against the young boys he had been coaching. He continued working in football with access to countless young boys (many of whom alleged similar misconduct) until he was found guilty of 45 charges of indecent assault in May 2019. The lengthy and extensive court proceedings may explain why this was the only case among the ones we tested in which people from the legal profession got involved in the conversation.

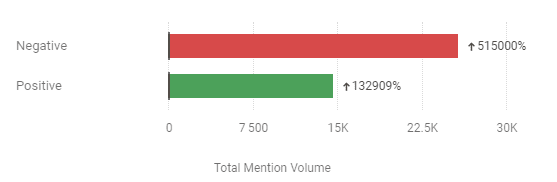

1,705 individuals talked about the guilty verdict and the case online, across 4,667 mentions. This represented a gender split of 63% men and 37% women, and much of the sentiment was negative with words used by men including “breaking”, “finally” and “Bob Higgins’ victims”. Perhaps unusually for posts dominated by men, the ‘green heart’ emoji was the most popular, followed by the ‘flexed biceps and ‘folded hands’ emojis. The general sentiment was that of brotherhood and solidarity with the survivors of the abuse.

Lizzy Dening says the gender split for this case might be explained by our ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. “Men might find it hard to imagine being a woman raped on a date or by their husband, but they do perhaps remember being a small boy at a football club. They remember the trust that they (and their parents) placed in the hands of their coaches and teachers, and perhaps look back and realise they were in a potentially vulnerable position. We must hope that understanding one type of sexual abuse might eventually translate into a deeper understanding for all survivors.”

How successful was the #MeToo movement?

The Me Too (or #MeToo) movement is a global movement against sexual harassment and assault. Although conceived in 2006 on MySpace by activist Tarana Burke, #MeToo became a worldwide phenomenon in 2017, following widespread allegations of sexual abuse against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein.

Due to the trivialisation of sexual harassment during his time in the industry, his crimes had remained relatively unspoken about for many years. It’s an example of ‘rape culture’, which Lizzy Dening describes as “an environment where general behaviour normalises or minimises sexual violence and rape.”

“It is tied up in our patriarchal society,” explains Dening. “Anything that supports the idea that men are more valid than women (from the pay gap to maternity leave expectations) has a knock-on effect that puts women’s needs and wants beneath those of men.”

So did the #MeToo movement prompt positive change in workplaces or public spaces? We looked at the hashtag ‘#MeToo’ over a six-month period starting exactly one year after Weinstein’s alleged crimes came to light: October 2018 to April 2019. Here’s how public sentiment about #MeToo has evolved:

First off, the number of people using the hashtag has decreased, from 136,000 unique authors to 86,000. Encouragingly, the gender split has evened out over the last year – from 60% women and 40% men to 52% women and 48% men. However, there’s been a decrease in positive sentiment and an increase in negative sentiment from both men and women.

“What was so powerful about the #MeToo movement was that it allowed anyone to share their story – whatever age, race, gender or background,” explains Dening. “It was such a simple, effective way to demonstrate both the scale of the problem, and also that sexual violence affects a variety of people, not just those who the media tend to represent.”

Delving deeper into the specific emotions expressed by those who posted online, anger, fear and surprise have all seen an increase, with the first two seeing over 10,000 mentions a piece. In contrast, disgust, sadness and joy have seen decreases, although disgust remains the top-felt emotion at 42,610 mentions. Sentiments of disgust were expressed when empathising with survivors’ stories, reacting to the persistent denials from posters unwilling to believe the accusations, and reacting to alleged perpetrators avoiding jail time.

In terms of the words and emojis most popularly used, women were most likely to say, “Amber Heard” and “Join” while men focused on “EU” and “Trump”. Compare that to a year earlier, when women were more likely to use the phrases “sexually assaulted or harassed”, “domestic abuse” and “sexual harassment” while men were more likely to use the words “true story” and “women” (although “Trump” still made an appearance).

The ‘purple heart’ was a popular emoji with 836 mentions, and often used alongside mental health awareness messages. Other popular emojis included the ‘face with tears of joy’ (754) and the ‘thinking face’ (707). The latter demonstrates an encouraging engagement with the issues that have been propelled into the public consciousness at an unprecedented scale thanks to ‘#MeToo’.

And yet, while the movement has raised awareness and provoked a conscious shift in attitude towards sexual assault, it’s yet to prompt improved support for victims. Dening points out that, “like most big news stories about sexual violence, the new demand for services hasn’t been reflected in funding to rape crisis centres.”

Methodology and glossary

This research was gathered in December 2019 through the social listening tool Brandwatch. For each chosen case, Google Trends was used to determine the date at which the number of online conversations were at their highest. A six-month period from this date was analysed using a query string that included all the words relating to the case while excluding irrelevant words that may be accidentally picked up in the query. Factors that were analysed included the gender split, the topics addressed, the words and emojis used and the sentiment and feelings expressed. The definitions of the emojis were taken from Emojipedia.org. Below is a short glossary of terms:

- Total mentions: counts every post that is relevant to the query created

- Unique authors: each unique individual that posted something relevant to the query

- Sentiment: the tool analyses each post for tone and intention, determining whether it exhibits a negative sentiment or a positive sentiment

- Emotion: using machine learning, the tool analyses each post for the type of emotion it exhibits, assigning either anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness or surprise.

It’s important to listen with empathy and understanding to the stories and experiences shared by those who have survived sexual abuse. Whether you’ve experienced sexual abuse or know someone who has, the approachable and understanding specialist abuse team at Bolt Burdon Kemp are ready to listen to what you have to share, and will work with you to figure out the best way we can help. Contact us for a no-obligation chat when you’re ready.

Expert bio

Lizzy Dening is a journalist for various national titles, and founder of Survivor Stories – a collection of interviews with survivors of sexual violence presented, crucially, in their own words. Dening is also co-Vice Chair of the Peterborough Rape Crisis Care Group.